- Polls apart - 4th March 2026

- Repeating on you… - 4th March 2026

- History man - 3rd March 2026

Warning: This article contains spoilers about Game of Thrones series seven, episode 1.

Game of Thrones is back – and the female characters are at the forefront of the action. Sansa Stark is still struggling to control her bastard brother Jon Snow, yet remains vulnerable to her Machiavellian adviser, Littlefinger. Her younger sister, Arya, has loosed a vengeful killing spree on the treacherous Frey family, and Daenerys Targaryan, claimant to the Iron Throne, has finally set foot on Westeros – with dragons in tow.

[amazon_link asins=’B018SBS8OW’ template=’ProductAd’ store=’thebridgegall-21′ marketplace=’UK’ link_id=’ae03b586-6fbd-11e7-b8bc-59689f119c50′]In the apocalyptic close to the previous season, the scheming matriarch of the ruling Lannister family, Cersei, obliterated her religious opposition, her smug daughter-in-law, Margaery, and a large chunk of the population of King’s Landing in a murderous, explosive fire. Her last surviving child – the “traitorous” King Tommen – killed himself, leaving her to take the Iron Throne. An unrepentant killer, up until this point Cersei’s love for her children was her one redeeming feature. Now childless, the audience can only wonder what Cersei will do next.

Anxieties about women, motherhood and power are nothing new in the history of Western society. In medieval Europe, queens usually had limited powers while their husbands lived because of the perceived authority of husband over wife in the medieval church.

As a widow, a woman had no right of succession, though she might confer power to a new king – thus Cnut, the Danish warlord who conquered England, married Emma of Normandy the widow of Aethelred II. If a woman was mother to a future heir, she might enjoy a brief spell as regent until the child came of age. But even women with legitimate inheritance claims had problems establishing themselves. Henry I’s decision to designate his daughter Mathilda as his heir left England and Normandy wracked by civil war between 1135 and 1152.

Queen in her own right

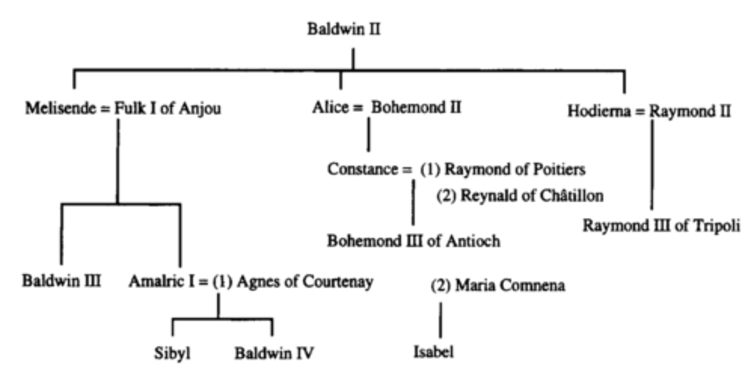

Queen Melisende of Jerusalem enjoyed more success, for a while anyway. Melisende was the eldest of four daughters produced by King Baldwin II of Jerusalem, who had settled in the Holy Land after the first crusade. In 1129, Melisende married a rich Western ruler, Fulk V of Anjou. When Baldwin II died in 1131, he made the unusual step of designating Fulk, Melisende and their young son Baldwin III joint heirs – perhaps because he feared Fulk might try to rule without her.

Wikitree, CC BY

This unusual constitutional position caused problems. Fulk tried to exclude Melisende from power and appointed many of his cronies to top jobs. She retaliated by fraternising with her popular cousin, Hugh II of Le Puiset, who rebelled against the king. Hugh was sentenced to exile, but was violently attacked before he could get away.

Melisende was furious – even the king was not safe among her supporters. Hugh’s attacker claimed he had acted independently in the hope of gaining Fulk’s favour. In a manner fairly reminiscent of Game of Thrones, Fulk had the knight maimed – all his members were mutilated apart from his tongue so he could continue to proclaim the king’s innocence.

Surprisingly, equilibrium between the couple was restored. Melisende resumed an active role in government, and Fulk agreed not to make decisions without her. If Game of Thrones’ Robert Baratheon had tried this tactic with his queen, Cersei Lannister, her character might have developed very differently.

In 1143, Fulk met a similar end to Robert Baratheon – in a “hunting accident” – though there is no evidence of foul play. Portrayed as a grieving widow, Melisende was ready to resume power with her 13-year-old son Baldwin III.

Regency and motherhood

Acting as regent for a child or an absent husband was one of the few opportunities in medieval society for women to wield political power. But Melisende was a claimant in her won right, and reinforced their dual dynastic authority by being crowned again with her son. She was an experienced and skilful ruler, but by 1150 the relationship between mother and son had soured.

Histoire de la Guerre sainte par Guillaume de Tyr, avec la première continuation

Ambitious nobles accused the king, who had already reached an age suitable for majority, of immaturity. They said that Baldwin was hanging “from his mother’s teat”. In around 1152, Baldwin demanded that the queen split the kingdom with him, then promptly invaded her half.

Although Melisende lost the ensuing civil war, she had significant supporters including the patriarch of Jerusalem – which suggests that her claim was treated seriously. The conflict lasted a few weeks – but, unlike Cersei, Melisende was a pragmatist and quickly rebuilt communications with her son. She agreed to give up the throne and from 1153 to her death in 1161 she supported Baldwin, including coordinating a military campaign in 1157.

Modern parallels

Much has been made of the general influence of the medieval past on Game of Thrones (see, for example, Carolyne Larrington’s Winter is Coming) but Cersei would have been unlikely to rule in the medieval world as the widow of a “usurper” with no explicit claim to power through inheritance or regency, even if she married again.

Meanwhile, Daenerys, a Targaryan claimant currently rendered barren by a curse, might also have struggled without proof of her fertility – though her portrayal as “mother of dragons” attempts to address this anxiety. And, to be fair, the dragons make formidable surrogate children.

Some argue that we should avoid using Game of Thrones to get students talking about the medieval past as it has nothing to do with “real” history. But in July 2016, Theresa May became prime minister elect when Andrea Leadsom withdrew from the Conservative Party’s leadership contest after her remarks about motherhood and the ability to wield power.

Whether reflecting on medieval society as an academic exercise, or enjoying modern fantasy fiction, we should examine why our conceptualisations of women in power are still so strongly governed by their relationships to men and children.

Natasha Hodgson has previously worked on two AHRC funded projects relating to medieval history: The Hull Electronic Domesday project (University of Hull) (2004-06) and PASE II (University of Cambridge) (2006-07).