- Cyber bullying - 6th March 2026

- Fight club - 5th March 2026

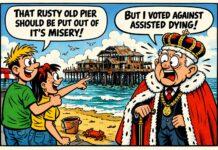

- Polls apart - 4th March 2026

Early in my writing and publishing career, I was invited to speak to an undergraduate class about research and interview techniques. One of the student questions was, “How do you get important people to respond to an interview request?”

I failed to offer any advice beyond the obvious: Write a good request letter. The professor jumped in, as this was a problem that annoyed her as well. It seemed the students—by the very fact of being students—had difficulty getting their requests taken seriously. How could they overcome that hurdle?

The question stymied me—why wouldn’t someone respond to a polite request? Back then, I responded to every email and request I received when working at a publishing house, as it was flattering to receive any attention at all. Perhaps it helped this was during a different era of email, around 2000 or 2001, prior to social media, when I was still crafting emails the way I did handwritten letters—long, drawn out affairs. I was still eager to check my inbox.

Today, even before I open my email, my blood pressure spikes thinking of all the requests, problems, and complaints I’m likely to find. And I receive at least one or two requests per week from students who are researching a dissertation or class assignment.

“What is the future of publishing?” they ask. Or, “How has the publishing industry has changed over the last 10 years?”

Often, I don’t respond. Recently, though, I did, to a brief and well-written request, and when the follow-up came, it was about 15 very generic industry questions—probably sent to half a dozen other people as well. Answering them thoughtfully was going to consume an entire afternoon. I was immediately sorry I had let down my guard. What was my responsibility to this person?

Last week, I read a post by Steven Pressfield: Clueless Asks. Pressfield is the author of The War of Art, as well as the more recent Turning Pro—some of the best insights into writer psychology. Pressfield defines clueless asks as requests coming from strangers who send him unsolicited work, want to schedule a “pick your brain” lunch meeting, or ask questions they could find the answers to themselves (among other things). He writes:

These are not malicious asks. The writers who send them are nice people, motivated by good intentions. They’re just clueless. They have committed one of two misdemeanors (or both). First, they have demonstrated that they have no respect for my time—and no concept of the value of what they’re asking me for. … The real ask in these cases is “Can I have your reputation?” In other words, “Will you give me, for free, the single most valuable commodity you own, that you’ve worked your entire life to acquire?”

As someone on the receiving end of many clueless asks, what Pressfield says resonates with me deeply. His post is the sort of thing I might have written, and certainly not a week passes when I don’t privately share a clueless ask with my partner and express frustration. But Pressfield may be letting us both off the hook a little too easily.

First, and most obviously, this is a complaint of the successful and privileged few. Airing such a complaint can be a terrible idea, as few are likely to be sympathetic (except other successful people). If you read the comments under Pressfield’s post, you’ll see what I mean.

I’m sure he’s accepted that “clueless asks” are a feature of the successful person’s life. You don’t get the good parts without the more annoying. Yet at some point (it’s irresistible), it seems every successful person (at least those who blog) eventually write a post that can be summed up as: “Please, for the love of God, be smarter about the questions or asks you’re making.”

The thing is, it’s pretty rare that one’s pleas will reach the people who need to hear it or would listen. It reminds me of a similar phenomenon with agents who never stop admonishing: “Read the submission guidelines! Only submit what I actually represent!” It’s a valid admonishment, but probably 99 percent of writers who go to conferences or read publishing guidebooks know that already. The majority of queries that agents receive are from people who will never attend a conference or educate themselves on proper etiquette. But because it’s the thing that annoys agents day in, day out, they can’t help but admonish the people whose ear they do have.

This doesn’t answer the question, though, of what responsibility the successful might have toward others—or what is owed. Here, I likely diverge from Pressfield. What authority, status, and success I have is partly (maybe wholly) the result of those who have granted it to me. If I am a publishing expert, it’s because you say or believe I am. I’m reminded of an Alan Watts lecture, where he says:

You can’t talk about a person walking, unless you start describing the floor. Because when I walk I don’t just dangle my legs in empty space. I move in relationship to a room. So in order to describe what I’m doing when I’m walking I have to describe the room, I have to describe the territory.

So in describing my talking at the moment I can’t describe this just as a thing in itself because I’m talking to you. So what I’m doing at the moment is not completely described unless your being here is described also. … We define each other, we’re all backs and fronts to each other. We and our environment, and all of us and each other are interdependent systems. We know who we are in terms of other people.

What I have was not created solely through my own hard work. My reputation is not something I own; it is something that has been formed and granted over time within a community. And I have a responsibility to that community—to help others and share what I have. It also helps to remember what it was like when no one answered my emails (yes, I’ve made some clueless asks myself). The clueless asks never go away, but perhaps there’s a better way to handle them than to judge or dismiss them entirely.

There’s a saying, attributed to Malcolm S. Forbes: “You can easily judge the character of a man by how he treats those who can do nothing for him.” Assuming for a moment this is true, then in the Internet age, how could one live up to this maxim without considerable sacrifice, given how easy it is for public figures to be exposed—and expected to respond—to the communications of the many? There is no easy answer that I can see, but at least we can reflect on and recognize what choices we make—where we draw the line.

Without question, my contact page pushes against the clueless ask. It states that if it takes me a few minutes to respond to a message, I will; if it really requires a business transaction (a consultation), then I will not.

That said, anyone—including myself—who receives clueless asks already knows the most frequently asked questions. They know the pattern of request. And that makes it straightforward to create standard responses that can be sent in less than a minute, even by an assistant, that offer next steps, resources, and information on how the asker can help themselves. Maybe it’s a small thing, but at least it’s acknowledgment. Yes, I see you. You exist.

This is not to say that I am doing better than Steven Pressfield, or that he is abdicating responsibility in some way. Most authors choose specific and meaningful ways to give back to the community, and answering unsolicited emails can be a thankless, invisible, and time-sucking task. Still, for the community of people I reach, email is the tool of those of very little means, and I feel I’m doing some good through those I do answer.

As far as the student who sent me the 15 generic questions, I did respond. I didn’t respond to every question, and sometimes I simply linked to relevant and publicly available articles I’ve written. I did what I could to meet her halfway. It seemed a good compromise.