- Honours even - 7th January 2026

- Football focus another trial - 6th January 2026

- A year to forget… - 5th January 2026

For our Editor, Welshman Phil Parry a free and independent media as well as official respect for human rights, are essential, although they do not exist in many states around the world, and he looks back at a year when the situation has become WORSE not better in numerous places.

I try to be positive, but sometimes it is difficult.

As a journalist when I look at what is happening around the world I hold my head in my hands because 2025 has been so bad, and, I’m afraid, 2026 is unlikely to be much better.

This is the case, sad to say, for a free media (which is important to me), and for a respect for human rights – both of which are being eroded everywhere.

This is the case, sad to say, for a free media (which is important to me), and for a respect for human rights – both of which are being eroded everywhere.

In the EU there is official recognition of media freedom with it saying: “The European Commission adopted today a European Media Freedom Act, a novel set of rules to protect media pluralism and independence in the EU. The proposed Regulation includes, among others, safeguards against political interference in editorial decisions and against surveillance…”.

The EU is better than most places, but even here these fine words belie the reality.

For example, after Slovenia seceded from Yugoslavia in 1991, it gave Radio Television of Slovenia (RTV-SLO) a mandate to report independently, unlike the state propaganda that passed for news under communism. Yet the Government there is now refusing to pay RTV-SLO’s budget, and wanted to pass a new media law that will make it easier to control.

In the Netherlands the situation appears to be just as bad. Reporters on the national public news broadcaster, the NOS, have been physically attacked at protests, and while reporting on Covid-19 measures. The NOS removed its logo from its satellite vans after they were repeatedly harassed in traffic.

In Latvia, the chief risk is the legal and financing structure. The country’s new public-media law failed to include a set-aside tax, like the television licence fee that funds the BBC (which could now be cut after the Martin Bashir affair), and that leaves it vulnerable to political pressure, while it is not clear that the supervisory board will be protected from political appointments.

When Viktor Orban won power in Hungary in 2010 he adapted Vladmir Putin’s blueprint, transforming the state media agency MTVA into a propaganda organ. The group was restructured into a shell company in a fashion that exempted it from the law governing public media, and during the European Parliament (EP) elections in 2019, editors at MTVA were recorded instructing reporters to favour Mr Orban’s Fidesz party.

Poland’s Law and Justice (PLS) party followed Mr Orban’s example when it won power in 2015, and quickly turned TVP, the public television network, into a bullhorn for the party.

The network championed campaigns against gay rights and demonised the opposition mayor of Gdansk. After he was assassinated by an extremist in 2019, a court told TVP to pay damages, but it did not comply.

However outside the EU, the problems facing an independent media are even worse.

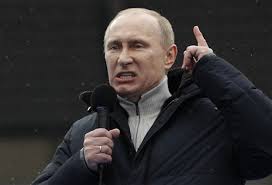

The prime example, of course, is Russia where RT (Russia Today) is accused of being a mouthpiece for Mr Putin. By the mid-2000s Russian news shows’ agendas were being set at government-led meetings.

Mr Putin signed a law that allows Russia to declare journalists and bloggers “foreign agents” in a move that critics say allows the Kremlin to target government critics.

Under the vaguely worded law, Russians and foreigners who work with the media or distribute their content and receive money from abroad would become ‘enemies of the state’, potentially exposing journalists, their sources, or even those who share material on social networks to foreign agent status.

In Belarus the situation is also appalling. At least 16 journalists there are behind bars, and riot police are singling out reporters for arrests and beatings at protests as the media is intimidated.

These sort of outrageous things are inextricably bound up with human rights, but in 2025, these rights faced significant challenges from rising authoritarianism, conflicts, and climate crises.

The UN’s Human Rights Day theme “Human Rights, Our Everyday Essentials“ focusing on the relevance of crucial human rights in turbulent times, highlighted issues like gender equality, digital rights (AI), and the need for accountability, while youth-led protests emerged globally, pushing for reform against crackdowns.

The UN’s Human Rights Day theme “Human Rights, Our Everyday Essentials“ focusing on the relevance of crucial human rights in turbulent times, highlighted issues like gender equality, digital rights (AI), and the need for accountability, while youth-led protests emerged globally, pushing for reform against crackdowns.

There has been a need to reinforce international law, protect an independent judiciary inside countries, combat misinformation, and allow free speech.

Let’s take another important country where these issues appear to have gone BACKWARDS – China.

An estimated one million Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities were detained in ‘re-education’ camps during a security crackdown there from 2017 to 2019.

Some of the camps have been shut down, and others converted into factories or prisons, but many inmates were then sent to do forced labour or imprisoned further, so 2025 has been especially bleak.

Uyghurs who went abroad were cut off from their families; many sought asylum in countries such as Canada, where governments fast-tracked settlement processes for them. But ow Uyghurs who fled, are losing protections as China pressures other countries to hand them over, and as America and Europe have grown more hostile towards refugees.

China promotes Xinjiang as a tourist paradise (and a safe place to which Uyghurs should return), with its authorities denying that any human rights abuses have ever occurred in the province. However such comments have been condemned as a total lie by human rights activists.

But it isn’t just in China that the situation should be condemned.

As a journalist I know only too well that brave colleagues everywhere have to watch their step as they expose facts the authorities don’t like, with 2025 looking particularly bad.

Unfortunately 2026 doesn’t look much better…

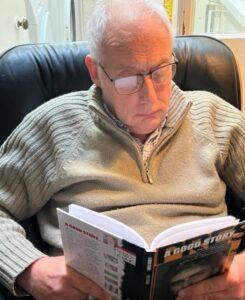

The memories of Phil’s astounding, decades long award-winning career in journalism (when he has always worked in a largely free environment) as he was gripped by the rare neurological disabling condition Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in a major book ‘A Good Story’. Order it now.

Tomorrow – how news that football’s governing body being accused of a “monumental betrayal” by fans after it emerged that the cheapest tickets for the summer’s World Cup final were to cost more than £3,000, has focused attention on huge earlier controversies – some of which surfaced when Wales qualified.