- Eyes right… - 26th February 2026

- Opposites attract - 26th February 2026

- Upset coffee - 25th February 2026

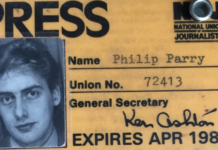

During 23 years with the BBC, and a 41 year career (when he was trained to use clear and simple language, avoiding jargon), our Editor, Welshman Phil Parry, always knew that any journalist (especially an investigative one like him), should be up to speed with the law, yet he is shocked at how long legal resolutions can take, and new research suggests that it is taking longer.

The truth is even stranger than fiction.

Dickens stories are nothing compared to what is actually happening.

The case of Jarndyce v Jarndyce in Bleak House for example was interminable, becoming a brilliant send up of the time taken by lawyers in the legal system then (in the mid 19th century). It turned into a byword for seemingly endless legal proceedings.

However the reality is little better now.

The libel cases I have been involved with in the past (and there have been several – all of which were thankfully successful) took YEARS, but they appear to be becoming even longer today.

The result is that I am nervous about consulting our lawyer (although I always do so), as apart from the cost, I know it will take an awfully long time if he then takes court action. So before I go to him I am secure in the knowledge that I am clear myself about what can and cannot be said, because after many years in journalism I realise only too well it is vital that what you publish is safe, because “Justice delayed is justice denied” – a crucial legal maxim.

In other countries it is even worse (if you can believe it!) and that has a huge negative effect on their economy.

India for example, has consistently fared worse on composite measures of justice than several of its peers, including Indonesia, China and Vietnam, according to the World Justice Project, a research outfit.

On a specific indicator of judicial speed, India ranked 131 out of 142 countries, below Pakistan and Sudan.

According to the India Justice Report (IJR), the courts’ backlog is expected to increase by at least 15 per cent by 2030.

India’s judiciary is not just in a “mere state of stasis but a downward spiral”, declares Gautam Patel, a former judge of the Bombay High Court (BHC).

India’s judiciary is not just in a “mere state of stasis but a downward spiral”, declares Gautam Patel, a former judge of the Bombay High Court (BHC).

At every level, judges are hindered by archaic rules.

Mr Patel complains that he has had to assess district judges on their punctuality and courteousness, despite never seeing them in court.

The Indian judiciary is also overworked and understaffed.

Nearly a third of judge positions and a quarter of support staff roles in high courts are vacant.

But even at full strength, the caseload would never be cleared because of new cases constantly being filed.

The consequences of this malaise are vast.

Around 75 per cent of India’s prisoners are awaiting trial, the sixth-highest share in the world.

Judicial delays also have enormous economic impact.

In addition to legal expenses, people face the opportunity cost of forgone wages. These alone amount to at least 0.5 per cent of GDP in a year.

Firms are even bigger economic victims. Many are dragged into long disputes, often over basic contracting issues.

In 2019 the World Bank (WB) estimated that enforcing a contract in India can take roughly 1,500 days (a little less than four years), compared with under 500 in the rich world and China.

India’s courts are no longer an instrument for resolving disputes between parties, but one for buying time, proclaims Arghya Sengupta, founder of the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy.

In 2024 the lower courts disposed of 23 million cases, even as 25 million were added, and clearing that backlog would require a 40 per cent productivity increase, sustained over five years.

Luckily jail has never been a concern for me, just a heavy fine, although even that has been avoided because of thorough legal checks.

The length of time the legal process takes, though, IS a worry.

It seems to be getting longer too…

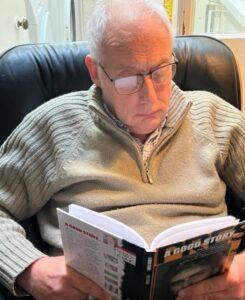

The memories of Phil’s astonishing, decades long award-winning career in journalism (when ensuring safety against legal action was vital and relatively quick) as he was gripped by the rare neurological disabling condition Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in the book ‘A Good Story’. Order it now.