- Death wish - 23rd February 2026

- Return to sender - 20th February 2026

- Legal eagle - 19th February 2026

During 23 years with the BBC, and 41 years in journalism, a major factor has driven many of the stories covered by our Editor, Welshman Phil Parry – population growth.

New figures again showing numbers are declining relatively in many countries, and that fatuous official measures are being taken to force women to have more babies, underline this salient fact.

Officials (like journalists) know the importance of a key factor in society.

DEMOGRAPHY, or to be more precise, a growing population.

These officials understand how central it is for a huge number of things in their country (such as the economy), so they make absurd and largely unsuccessful attempts to boost it, while for reporters population growth lies at the heart of an enormous number of stories.

For example, ones about families being forced into sub-standard accommodation because they were the only places available to rent?

Demography.

Overcrowding in housing leading to appalling examples of domestic violence?

Demography.

A stretched police force trying to monitor growing levels of crime in a large area, resulting in terrible mistakes?

Demography.

Let’s take China where the government is trying to row back on its controversial ‘one-child policy’, and now uses blunderbuss methods to try to force women to have babies they may not actually want.

Demographers estimate Chinese women have one child each on average, far below the 2.1 needed to keep the population stable.

After decades of making unscientific claims to deter baby-making (such as that pregnancy reduces a woman’s intelligence), the authorities are now arguing the opposite.

On October 30 a magazine overseen by China’s National Health Commission (NHC) published an essay on “the four benefits of childbirth”, including increased brainpower and lower risk of cancer and menstrual pain.

Online, this prompted a rapid backlash.

“To get people pregnant, the government will literally come up with anything they can”, fumed one writer.

In late October the State Council (SC), China’s ‘cabinet’, unveiled a sweeping set of pro-natalist measures, including child tax credits, more maternity and paternity leave, as well as easier access to housing loans, which is a big concern for Chinese families.

The picture of a one-child family that used to be on the cover of school textbooks for eight and nine-year-olds has been replaced by one showing a pregnant mother and her two children.

The school curriculum is being adjusted to stress the virtues of family and marriage, and the government has also called for the production of more TV shows that extol the virtues of having youngsters.

One woman received questions such as these from a Chinese official: “When was your last period?” “Are you pregnant?” “Do you plan to have a baby?”.

She declared: “It doesn’t seem like the kind of thing that could happen in the 21st century”.

But all these measures are unlikely to work, because as countries from Singapore to Sweden have found, a decline in fertility rates is very hard to reverse.

At least, though, they know how crucial is demography to a whole load of things.

As do journalists like me!

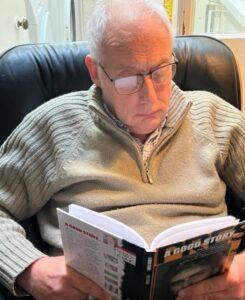

Phil’s memories of his extraordinary award-winning career in journalism (when demographic changes drove a lot of his stories) as he was gripped by the incurable disabling condition Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in the major book ‘A GOOD STORY’. Order it now!

Tomorrow, he looks at the severe jail sentences given by Chinese authorities to democracy protesters in Hong Kong, where the entire case has been widely criticised as politically motivated.