- Sorry is the hardest word… - 4th February 2026

- Car trouble - 3rd February 2026

- ‘Ch-ch-changes’ copyright D. Bowie - 2nd February 2026

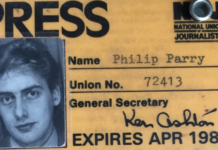

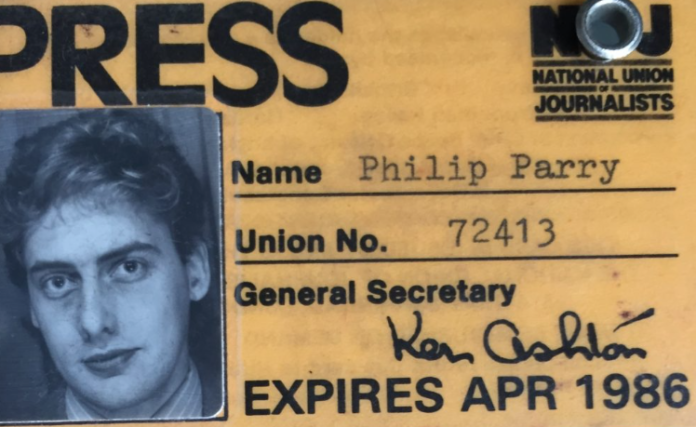

During 23 years with BBC Cymru Wales (BBC CW), and 41 years in journalism (when he was trained to use clear and simple language, avoiding jargon), our Editor Welshman Phil Parry has always known that stories are governed by legal rules, so he welcomes more evidence that the court system is now opening up to reporters like him.

It’s a fundamental plank of a democratic society that those accused of crimes should face publicity.

But this golden rule remains under pressure today with fewer and fewer court cases being reported (when I started in journalism there were dedicated reporters for Magistrates as well as Crown Court), although there are some grounds for optimism.

Let’s take the example of family courts.

Every year they make critical decisions about children’s care, surrogacy, divorce and domestic violence.

Yet until relatively recently this has largely happened behind closed doors.

Before 2009 journalists were banned altogether, and even after that tough restrictions meant few bothered trying to get in.

In the past two years, though, a pilot project has improved access, and from January 27 the scheme will be widened to be made permanent.

There will still be huge safeguards, however, and journalists need to be aware of them.

There will still be huge safeguards, however, and journalists need to be aware of them.

Any reporter who breaches confidentiality rules could face a fine and contempt-of-court proceedings.

To attend a case journalists will need a judge’s permission, which can be refused if there is a good reason, and they will be told to keep the identities of families and children anonymous.

Public-law cases (such as local authorities applying to take children into care) will be opened up first, and private-law cases (for instance courts resolving parental disputes over children) and those overseen by magistrates will follow.

Public-law cases (such as local authorities applying to take children into care) will be opened up first, and private-law cases (for instance courts resolving parental disputes over children) and those overseen by magistrates will follow.

There is another pilot for financial-remedies cases, in which separating couples split their assets.

The change will bring much-needed transparency to courtrooms that transform thousands of lives each year.

This matters for several reasons.

Around £1.5 billion of taxpayers’ money is spent administering courts of all types each year.

Openness could also help raise public confidence.

The children and families seeking help from judges and barristers are often vulnerable; they need at least to trust that they will be treated fairly.

Raising public awareness will be important, too, argues Dr Julie Doughty, a trustee of the Transparency Project (TP), and a senior lecturer in law at Cardiff University (CU).

“A lack of openness undermines accountability and allows occasional poor practice to continue unchecked”, concluded a review by Sir Andrew McFarlane, president of the family division.

This is a step in the right direction, although there is still a great deal of work to do, not least in the area of anonymity for those accused (or convicted) of sexual abuse offences, and breaching reporting restrictions is a criminal offence.

Reporting restrictions which are available to those under 18 include the following:

- Section 49 of the Children and Young Persons Act 1933 (CJPA 1933) which provides for automatic reporting restrictions for those under 18 who are defendants or witnesses in criminal proceedings in the youth court and appeals from the youth court.

- A 1999 act mandates discretionary reporting restrictions for those under 18 who are defendants or witnesses in other criminal proceedings.

- To avoid the issue of reporting restrictions lapsing once a child reaches the age of 18, prosecutors may rely on this act, which offers discretionary lifelong reporting restrictions for victims and witnesses who are under 18 when the proceedings commence.

Another section provides a similar (discretionary, lifelong) power in respect of adult victims and witnesses.

Another section provides a similar (discretionary, lifelong) power in respect of adult victims and witnesses.

The Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act 1992 creates an automatic prohibition on the publication of details that identify a victim of rape or other serious sexual offences, and there is a similar provision in respect of victims of female genital mutilation under schedule one of the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003. There are also automatic reporting restrictions on certain pre-trial hearings.

So there is still a long way to go for journalists like me to ensure we stay the right side of the law, even if it’s now easier to report on events at a family court.

The memories of Phil’s decades long award-winning career in journalism (when legal rules were all important) as he was gripped by the incurable neurological condition, Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in a major book ‘A GOOD STORY’. Order it now!