- Dark speak easy part one - 18th February 2026

- X marks the spot again - 17th February 2026

- Wordy again part three - 16th February 2026

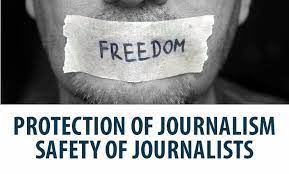

As our Editor, Welshman Phil Parry has written many times a free and independent media is essential for a functioning democracy, although this does not exist in many states around the world, and today more evidence is emerging of authoritarian countries cracking down on the free flow of information.

It is absolutely fundamental, but sadly evidence emerges almost every day of it being in retreat all over the globe.

I am talking here about media freedom, and as I have been a journalist for 42 years, I think I have a right to be concerned.

According to an index devised by Reporters Without Borders (RSF) (the global score of relative media freedom), it has regressed since 2014 from 67 out of 100 (where America is today) to under 55 in 2025.

‘For the first time in the history of the Index, the conditions for practising journalism are “difficult” or “very serious” in over half of the world’s countries and satisfactory in fewer than one in four‘, declares RSF.

We’ll start with the example of Serbia, where the situation is particularly worrying today.

KRIK, an investigative outlet (like The Eye) that often exposes graft in the Serbian government, has been hit with more than 30 lawsuits in the past few years, of which 17 are current, proclaims Stevan Dojcinovic, the editor, and he has to spend up to five days a month in court.

The state media accuse him of working for the CIA and for George Soros, a Jewish billionaire who is a constant victim of anti-Semitic, as well as conspiracy theory attacks.

Faked pictures of him with a gang boss have been circulated, as well as real, intimate photos meant to embarrass him.

“It has taken a huge, heavy toll”, Mr Dojcinovic states.

Meanwhile, all the terrestrial broadcasters are state-controlled or owned by friends of the right-wing populist president, Aleksandar Vucic, so they report what he wants them to.

Zoran Kusovac, a media consultant, recounts that a friend divorced her TV editor husband partly because she was sick of Mr Vucic’s nightly calls.

There are, though, many other instances.

“If we report on corruption…our journalists are doxxed”, declares Wahyu Dhyatmika, the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Tempo Digital, an independent news outlet in Indonesia.

One journalist there was sent a severed pig’s head; others have received dozens of unrequested food deliveries, a reminder that the bigwigs they report on know exactly where to find them.

Digital technology has changed what it means to be a journalist, allowing anyone with a phone to disseminate shocking footage to a potentially global audience.

Nasty regimes correctly see this as a threat, and have pushed back with broadly worded internet laws that can be weaponised against critics. Several ban the dissemination of ‘fake news’, which in some places means any statement the government denies.

A new law in Zambia criminalises the “unauthorised disclosure” of “critical information”, defined as anything that “relates to public safety, public health, economic stability (or) national security”.

An index by Freedom House (FH), an American think-tank, finds that internet freedom has declined worldwide for 15 straight years.

This is not just a case of autocrats turning off the internet during protests (as in Iran in January) or elections (as in Uganda in the same month).

This is not just a case of autocrats turning off the internet during protests (as in Iran in January) or elections (as in Uganda in the same month).

In the past year, half of the 18 countries previously labelled digitally “free” (out of 72 judged) grew less so. Globally the most consistent deterioration in the past 15 years was in a measure of “whether online sources of information are manipulated by the government or other powerful actors”.

In Russia you get a particular (Kremlin-sponsored) view of the world.

However there was no state WhatsApp until recently but Vladimir Putin filled this idealogical void with a site called ‘MAX’, a new ‘national messenger’ app created by a Russian firm closely controlled by the Kremlin.

WhatsApp (whose owner, Meta, is designated an extremist organisation in Russia) is especially popular with older people because of how easy it is to register and use.

The new one, though, is pre-installed on devices, although the concept clearly stems from Asia’s super-apps, and particularly China’s WeChat, which is a pillar of daily life there.

Some 1.3 billion people use it in China, not just for messaging but also for reading the news, booking travel, making medical appointments and paying bills.

But it is also an instrument for censorship and surveillance, restricting material critical of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Police use it to snoop on dissidents, too.

Mr Putin no doubt craves such a tool, but the public’s appetite for a Russian WeChat is less certain.

More than 36 per cent of Russians already use Virtual Private Networks (VPNs); software that gives access to blocked content by making a device appear as if it is in another country.

There are fears that the new app will allow the authorities to hack into the phone’s microphone or even its camera.

Sadly this falls into a familiar pattern in Russia where state news is deemed acceptable, yet information from independent sources is not, with information coming to light about undercover journalistic groups that play an important role in assisting the Ukrainian authorities, as they try to repel Russia.

Some of them (like The Eye) have NO state funding whatsoever, and operate on a purely freelance basis.

There is, for instance, InformNapalm.

This organisation was set up by journalists, an IT specialist as well as a dentist, and is proving to be a particular thorn in the side of the Russian military.

The InformNapalm.org website was created in March 2014 after the Russian military intervention in Ukraine and unlawful annexation of Crimea.

They’re all volunteers and they have conducted two major investigations into the shooting down of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, as well as gathered evidence about the presence of Russian troops on Ukrainian territory (which was denied by Russia).

They collect and analyse OSINT-information, found in open sources, including on social networks.

InformNapalm’s investigation of the then Russian 53rd Artillery Brigade commander Colonel Sergei Muchkayev, suspected of killing the MH17 passengers and other atrocities, was crucial.

Their involvement in subverting a publicity photograph was central in identifying members of the 960th Assault Aviation Regiment.

Independent journalistic websites in democratic countries around the world (whose investigations are heartily disliked by the Russian, Chinese, and Serbian authorities), include ones like Bellingcat.

It is a Netherlands-based investigative journalism group that specialises in fact-checking.

It was founded by British citizen journalist and former blogger Eliot Higgins in July 2014, and has published the findings of both professional and citizen journalist investigations into war zones, human rights abuses, and the criminal underworld.

In his first book Mr Higgins told how open source investigation has redefined reporting in the 21st century, and argued that the internet can be a force for good, despite bad actors, complacent technology firms and an explosion in alternative so-called ‘facts’.

The site’s contributors also publish guides to their techniques, as well as case studies.

he was killed

Bellingcat began as an investigation into the use of certain weapons in the Syrian civil war.

Its reports on the Russo-Ukrainian War (including the downing of the Malaysian flight), the Yemeni Civil War, the poisoning of Alexei Navalny and the poisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripal, as well as the killing of civilians by the Cameroon Armed Forces have attracted international attention.

More power to their elbow I say.

Sometimes all the abuse and empty legal threats I suffer (and Bellingcat, InformNapalm, as well as KRIK get the same) are worth enduring!

But try as hard as they might some authorities want to stop us doing our work, and telling the public what’s going on – Serbia is just one case of this appalling practice…

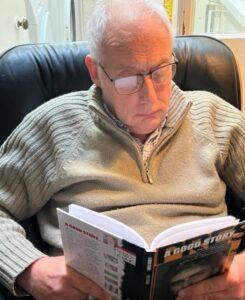

The memories of Phil’s astounding, decades long award-winning career in journalism (when investigations exposed huge wrong-doing, but abuse invariably followed) as he was gripped by the rare neurological disabling condition Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in a major book ‘A Good Story’. Order it now.

‘Dark speakeasy part two’ follows soon, where he looks at how new research shows there is a direct link between muzzling the media, and rising corruption in politicians.

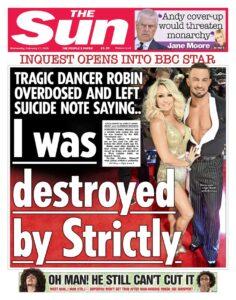

Tomorrow – shocking news that tragic former Strictly Come Dancing professional Robin Windsor, left a suicide note declaring that he had been “destroyed” by the BBC, puts centre stage their REFUSAL to answer The Eye’s questions about the huge number of scandals which have engulfed the giant corporation.

Tomorrow – shocking news that tragic former Strictly Come Dancing professional Robin Windsor, left a suicide note declaring that he had been “destroyed” by the BBC, puts centre stage their REFUSAL to answer The Eye’s questions about the huge number of scandals which have engulfed the giant corporation.