- Return to sender - 20th February 2026

- Legal eagle - 19th February 2026

- Round Robin - 19th February 2026

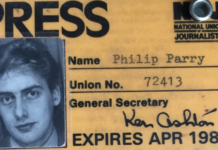

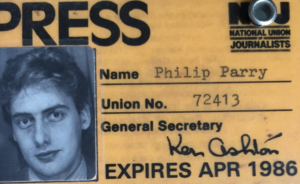

During 23 years with the BBC, and 40 years in journalism, for our Editor Welshman Phil Parry knowledge of the legal rules have been all important, and this is now highlighted by China saying accusations of massive cyber hacking were “fabricated and malicious slanders” when this description actually has a very specific definition in law.

I have sat numerous law exams because it is vital to have a knowledge of legal rules.

I have sat numerous law exams because it is vital to have a knowledge of legal rules.

There are an incredible number of them, but basic ones are knowing the difference between ‘slander’ and ‘libel’, as well as what the legal definition is of ‘malice’.

They are put centre-stage now by China hitting out at its accusers over alleged (another legal term) hacking.

Mark Kelly of Recorded Future, a cyber-security firm, says his company is aware of about 50 hacking groups in China.

Mr Kelly describes China’s cyber-espionage efforts as “orders of magnitude” greater in scale than those mounted by Russia or North Korea.

The West’s anxieties (not least about the hackers’ theft of corporate data) are becoming increasingly manifest.

In January the head of the FBI, Christopher Wray, said that China’s state-sponsored hackers outnumbered his agency’s cyber-personnel by “at least 50 to one”.

He added that China’s hackers are laying the groundwork for a possible Chinese strike, “positioning on American infrastructure in preparation to wreak havoc and cause real-world harm to American citizens and communities”.

So the response by China to all of this claiming they were “fabricated and malicious slanders”, is questionable to say the least.

The definition in a legal dictionary for “malicious” is as follows: ‘Malice is not to be understood in terms of “wickedness” but in terms of intention to cause harm or at least actual foresight that harm may result.

‘“Maliciously” is an element of various offences in the Offences Against the Person Act 1861, and where it is concerned with doing an act it means intending to cause the relevant harm or at least foreseeing the risk of causing that harm.’

The term “slanders”, however, is VERY different, and isn’t simply a more emphatic version of a ‘libellous defamation’.

A prominent law firm puts it this way: “Defamation is split into two legal bases that a person can sue for: slander and libel. Slander is defamation of a person through a transient form of communication, generally speech. Libel is defamation of a person through a permanent form of communication, mostly the written word”.

In other words if you slag off an identifiable individual in a pub packed full of people and they hear, it is ‘slander’, but if you slag off that person (without evidence) in an article which can be read, it is a ‘libel’ which may be provable in court.

If only rules like this were known about by China when they said accusations against them of enormous hacking were “fabricated and malicious slanders”!

The memories of Phil’s extraordinary decades long award-winning career in journalism (when knowledge of legal rules was vital) as he was gripped by the rare neurological disabling condition Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in a major book ‘A Good Story’. Order it now.

Another book, though, has not been published because it was to have included names.

Tomorrow – another important aspect of his journalism for Phil: exposing cover up, and how this is now underlined by the fall out today following the appalling massacre of innocent concert-goers in Moscow.