- Tears of a clown - 4th July 2025

- Best of enemies part one - 3rd July 2025

- Disabling protests again - 2nd July 2025

INTRODUCTION

We, at The Eye, have been investigating and exposing the extraordinary events at Swansea University, Swansea School of Management and the Llanelli ‘Wellness’ Village for a long time. This article details in forensic and scientific terms how these events reach to the highest level and corrupt the reputation and integrity of the university institution and even the science itself. We ask why this has been allowed to go on.

This article is republished with permission of the author, Dr. Patricia Murray. It was first published by Leonid Schneider in the Forbetterscience blog.

Dr Patricia Murray, is Professor of Cellular and Molecular Physiology at the University of Liverpool, UK. This article follows a previous article regarding the business activities of the regenerative medicine company Celixir, owned by Sir Martin Evans, winner of the Nobel Prize of 2007 and former President of the University of Cardiff, and the struck-off dentist Ajan Reginald. Much of the contents in that story must be credited to Dr Murray, who is also an activist for medical ethics and research integrity in regenerative medicine and played a key role in uncovering the extent of the trachea transplant scandal in the UK in the aftermath of the Paolo Macchiarini affair, which recently made main news in the UK (here and here).

Murray’s activities led to parliamentary investigations into the role of UCL (University College London) and their professors, primarily Martin Birchall, in two deadly trachea transplants (here and here) and into the attitude of the journal The Lancet. Three clinical trials were permanently suspended or terminated following Murray’s advocacy for patient safety, it is likely that related trials at UCL and elsewhere in UK were also postponed indefinitely because of that. There were retaliations: UCL’s business partners, the trachea transplant company Videregen, deployed lawyers against Murray and her colleague (read here and here), without any success though.

The questionable activities of the UK company Celixir, by Dr.Patricia Murray

Executive summary

I first came across Celixir (previously known as Cell Therapy Ltd) through a BBC Radio 4 programme about Brexit. The CEO of the company, Mr Ajan Reginald, was on the programme suggesting that a possible opportunity offered by Brexit would be to enable the UK to develop its own regulatory framework so that companies like his could accelerate the translation of cellular therapies to the clinic. Reginald went on to state the following:

“We have a lot of patients in the UK that could benefit from heart failure treatment….We invented the technology here [a cell therapy that Celixir calls ‘Heartcel’], we’ve developed the technology here, we’re based here, we’d love to be able to bring this medicine to UK patients as soon as possible.”

-

- He was struck off the dental register in December 2002 after the General Dental Council (GDC) found him guilty of serious professional misconduct and making dishonest claims for work he had not done.

- A 2012 media report indicates that he incorrectly presented himself as ‘Dr’ Reginald on several documents in the public domain, and was falsely described as having a PhD.

- He continues to incorrectly present himself as ‘Dr’ Trevor Ajan Reginald on web-based documents available at Companies House.

- He appears to have falsely presented himself as a medical doctor, as evidenced by the fact that he is listed as “Ajanthan Trevor Reginald, MBBS, London University, 1996” in the 2004 graduation programme of Northwestern University (USA). Reginald was awarded a dentistry degree in 1996 (BDS), not a medical degree (MBBS).

- In 2011 The Times reported that Reginald ‘stole’ a £1M idea from an autistic inventor.

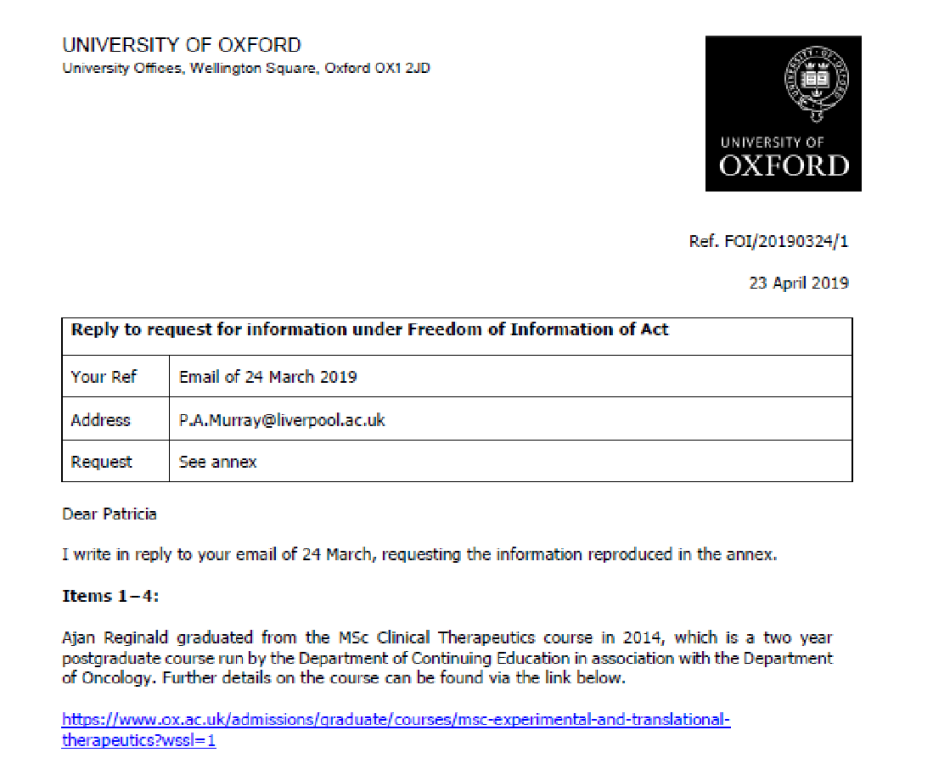

- In a research paper published in 2016, Reginald claimed to be affiliated with the University of Oxford.

In light of this history, I had some concerns that Reginald was now developing cell therapies for clinical use, and wanted to learn more about what was being planned in the UK. It appears that Celixir has already undertaken a clinical trial in Greece in 2012-2013 to test the safety of their proprietary cell type ‘immunomodulatory progenitor cells’ (iMPs) in patients undergoing cardiac by-pass surgery. Celixir now has approval from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and the London-West London & GTAC Research Ethics Committee Research (REC) (Reference number 18/LO/0020) to undertake a larger scale clinical trial at the Royal Brompton Hospital in London. On investigating the background to these trials, I discovered a series of disturbing facts. This report presents evidence that Celixir’s first patent (filed in 2011), and a promotional video made in 2014 to attract investors, appears to contain plagiarised and misrepresented research data. Moreover, it seems that the ‘iMPs’ used in the Greek trial in 2012-2013 may have been obtained from patients in the Morriston Hospital in Swansea, UK, without regulatory and ethics approval, and without having being prepared under the necessary ‘Good Manufacturing Practice’ (GMP) conditions.

The areas that will be covered are as follows:

- Background relating to Celixir’s clinical trials

- Questions relating to Celixir’s proprietary cell type, ‘iMPs’

- Issues relating to trial NCT01753440, undertaken in Greece 2012-2013

- Issues relating to the forthcoming trial NCT03515291 at the Royal Brompton Hospital

- Response of organisations to concerns and FOI requests relating to Celixir’s activities

- Celixir’s subsidiary companies, funders and supporters

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- References

- Appendices

1. Background relating to Celixir’s clinical trials

Celixir claim to have undertaken a clinical trial in Greece in 2012-2013 that tested the safety and feasibility of their proprietary allogeneic ‘immunomodulatory progenitor cells (iMPs)’(referred to as ‘HeartcelTM’), in eleven cardiac patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). This trial, which involved injecting ‘iMPs’ into the mycocardium, was registered as NCT01753440 on Clinical Trials.gov and the results were published in 2016. Celixir emphasises in the 2016 publication that iMPs are not mesenchymal ‘stem’ cells (MSCs).

Celixir now plan to undertake a Phase IIb trial to assess the safety and efficacy of the allogeneic iMPs in a trial involving 50 patients who will be undergoing CABG at the Royal Brompton Hospital in the UK (registered as NCT03515291 on Clinical Trials.gov). They have already obtained Clinical Trials Authorisation (CTA) from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and approval from the London-West London & GTAC Research Ethics Committee (REC). Of note, while the 2016 publication states that allogeneic bone marrow-derived iMPs were used in the Greek Trial, the initial entry on Clinical Trials.gov indicates that the cells were actually allogeneic mesenchymal ‘stem’ cells (MSCs) (tissue source not indicated). It thus appears that false information was included in the Clinical Trials registry. This raises the question of whether the ethics committee in Greece and the recruited patients were also given false information regarding the type of cells that were administered, but I do not have access to this information.

Intriguingly, on 3rd May, 2019, shortly after a report about Celixir was published on the ‘For Better Science’ blog, the following details on the the Clinical Trials.gov entry for the 2012-2013 trial were retrospectively changed:

- In the description of the intervention/treatment, ‘MSCs’ were replaced with ‘iMPs’

- the word ‘allogeneic’ was deleted from the description of the intervention/treatment

- primary and secondary outcomes were altered

- the number of patients was reduced from 30 to 11

- one of the Principal Investigators, Polychronis Antonitsis, deleted his name and contact details.

These changes are clear to see on the Clinical Trials.gov archive:

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/history/NCT01753440?A=1&B=3&C=Side-by-Side#StudyPageTop

The alteration to the Clinical Trials.gov registry suggests that Celixir did indeed use iMPs in the 2012-2013 Greek Trial. This raises some serious concerns because there is little information regarding the nature of iMPs, and there is no available evidence that preclinical experiments were undertaken to establish their safety and efficacy before they were used in patients in Greece.

2. Questions relating to Celixir’s proprietary cell type ‘iMPs’

Answers to the following questions were sought:

- what are iMPs?

- where were the iMPs used in the Greek trial derived from?

- what preclinical tests did Celixir undertake before administering iMPs to patients in Greece?

- were the necessary approvals from the REC, MHRA, and Human Tissue Authority (HTA) in place?

2.1 What are iMPs?

A report published by the investment research and advisory company, Edison, states that iMPs are derived from another of Celixir’s proprietary cell types called ‘progenitor cells of mesodermal lineage (PMLs)’ (referred to as ‘Myocardion’). Celixir filed a patent on the PMLs in July 2011. According to the patent, the PMLs can be isolated from mononuclear cells derived from bone marrow, but are preferably derived from peripheral blood. The co-inventors of this patent are Thomas Averell House, Martin Evans, Ajan Reginald, Ina Laura Pieper and Brian Perkins.

Celixir’s descriptions of their cell therapies are often contradictory. For instance, on their website, iMPs feature under the title “Stem Cells Could be Used to Treat Everything from Heart Disease to Menopause” and for reasons that aren’t clear, are defined in this article as ‘integral membrane protein’ rather than ‘immunomodulatory progenitor cells’:

“Because stem cells can differentiate themselves into a range of adult cells, they can potentially treat any disease or condition that causes and/or is perpetuated by the destruction of cells and tissues. At Celixir, we’ve focused our efforts on how iMP cells (Integral Membrane Protein) can treat patients with heart disease.”

But although the iMPs are sometimes described as ‘stem cells’, Celixir’s patents [here and here] clearly state that PMLs and iMPs “are not stem cells”.

The PML patent contains the following statements:

Firstly, “The PMLs of the invention are not stem cells. In particular, they are not mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). They are terminally differentiated”. I could not find any evidence for this assertion.

“The PMLs of the invention are preferably capable of migrating to a specific damaged tissue in a patient. In other words, when the cells are administered to a patient having a damaged tissue, the cells are capable of migrating (or homing) to the damaged tissue. This is advantageous because it means that the cells can be infused via standard routes, for instance intravenously, and will then target the site of damage.”

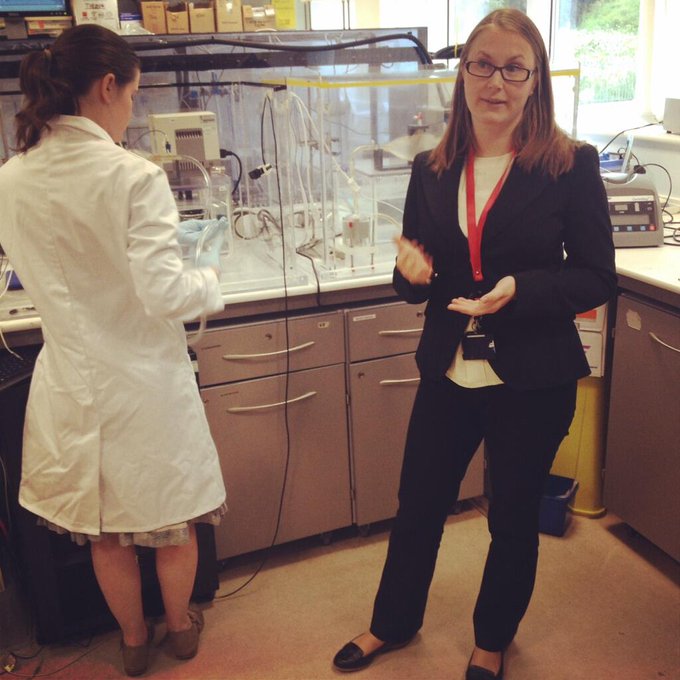

The data in Figure 5 of the patent are meant to show that Celixir’s PMLs can migrate to injured tissue following intravenous injection into a mouse with a fractured tibia.

However, these data have been plagiarised and misrepresented. The source of the data is a 2009 paper published by a US group, apparently unconnected with Celixir. Of particular note, the cells in the 2009 paper are in fact MSCs, and are not PMLs. This issue has recently been reported on the ‘For Better Science’ blog.

Despite the serious problems with this patent, according to Cell Therapy Limited’s (CTL’s) accounts for the year ended July 2015, in December 2012, the company granted a licence to the Chinese Company Alliancells Bioscience Co. Ltd for over £1M to exclusively utilise Cell Therapy Limited’s PMLs:

“On 20 December 2012, The Company (CTL) granted the right to apply for market admittance to exclusively utilise CTL’s autologous mesodermal stromal cell technology in Greater China. The amount received for this right to apply for market admittance was USD$1,682,392 […] That is approximately GBP£1,046,279. […] A licence fee of USD$6,000,000 is payable for use over 11 years, if and when, market admittance is granted”

The patent for the iMPs was filed in June 2015 by co-inventors Ajan Reginald, Martin Evans and Sabena Sultan. According to the PML and iMP patents, both cell types are prepared from mononuclear cells using identical protocols. Indeed, the protocols are so similar that even typographical errors are reproduced between the two patents [Appendix Table 1]. The description of PML and iMP morphology in the patents [here and here] is also identical:

“The iMP [or PML] cells of the invention are typically characterised by a spindle-shaped morphology. The iMP [or PML] cells are typically fibroblast-like, i.e. they have a small cell body with a few cell processes that are long and thin. The cells are typically from about 10um to about 20 um in diameter.”

Furthermore, the protocol described in the patents is just a standard protocol for isolating mononuclear cells and deriving MSCs.

For instance, regarding mononuclear cell isolation, the protocol begins as follows:

“Mononuclear cells (MCs) and methods of isolating them are known in the art. The MCs may be primary MCs isolated from bone marrow. The MCs are preferably peripheral blood MCs”

Regarding derivation of MSCs, the protocol states:

“Conditions suitable for inducing MCs to differentiate into mesenchymal cells (tissue mainly derived from the mesoderm) are known in the art. … These conditions may also be used to induce MCs to differentiate into PMLs [or iMPs in the case of the iMP patent] in accordance with the invention.”

It appears that neither patent contains anything new and one wonders why these patents were ever granted.

“Getting on to how we capture the value of our technology, we look at the cell surface receptors to characterise our cells. This is traditionally how companies look at the cells to not only understand what those cells can do but also to put intellectual property round them.”

“We look at 369 surface receptor markers […] versus the current competition which looks at only a handful of those markers, se we’re very highly characterising and protecting ourselves.”

It appears that Celixir’s strategy was to claim to have generated IP by simply analysing 369 cell surface markers on a single batch of iMPs (aka PMLs, aka PB-MSCs) on a single occasion. There is no IP here. Nevertheless, in 2016, Celixir licensed their iMP cell‘technology’ to the Japanese company Daiichi Sankyo for an upfront licensing fee of £12.5M.

In summary, the fact that Celixir’s PML and iMP patents have identical protocols suggests that they are in fact the same cell type. The protocols comprise standard methods for isolating mononuclear cells and then deriving MSCs so it is difficult to understand why patents were ever granted.

2.2 Where were the iMPs used in the Greek trial derived from?

According to Celixir’s 2016 publication, the allogeneic iMPs used in the 2012-2013 Greek trial were allegedly derived from the bone marrow of a healthy donor. It is not clear where the healthy donor was recruited from.

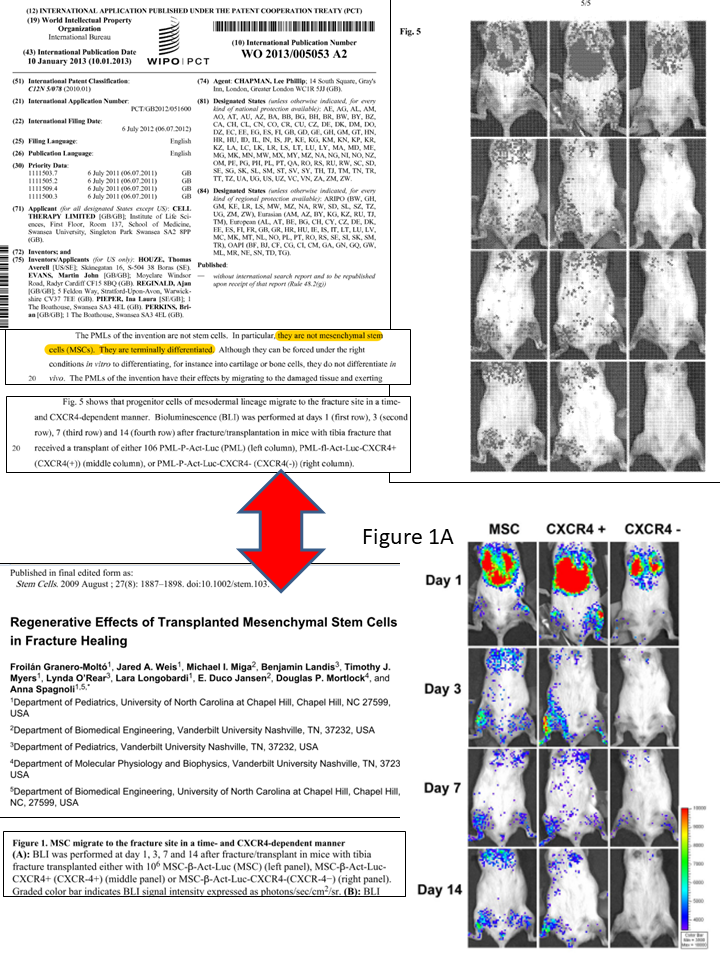

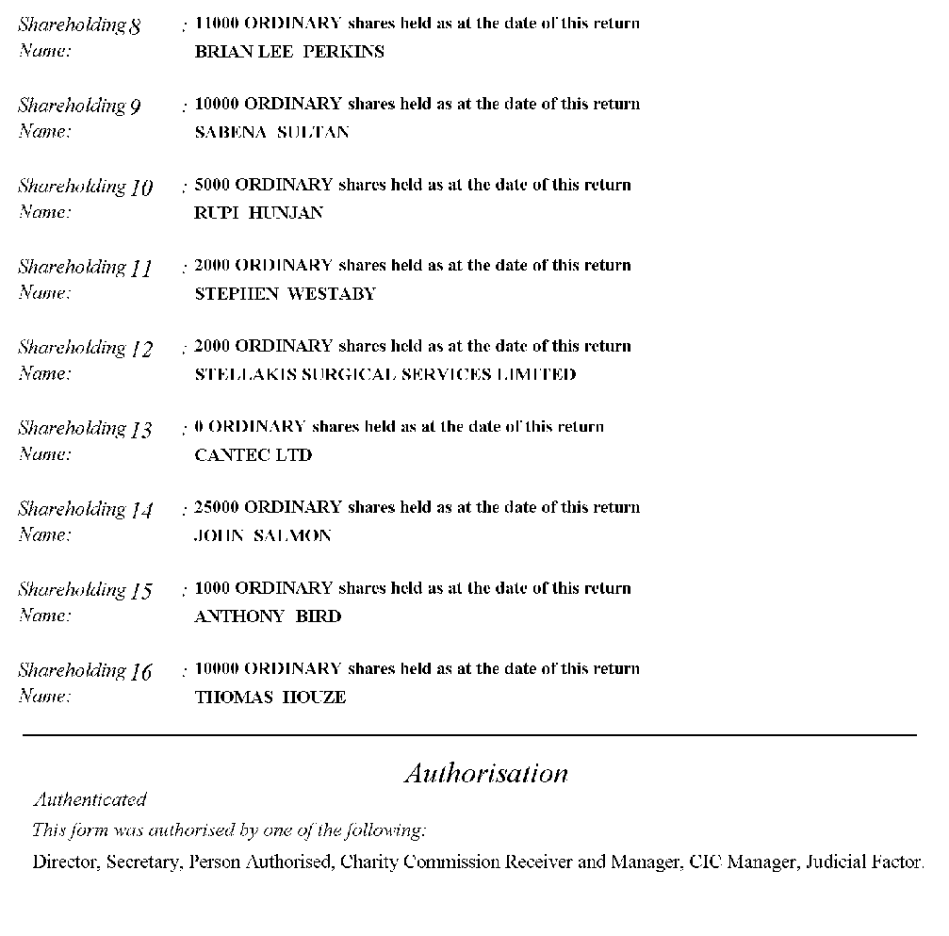

Images of the iMPs (HeartcelTM) are provided in a promotional video prepared by Celixir in 2014 to attract investors, and features businessman Lord Digby Jones (a remunerated Director of Celixir from November 2014 until January 2018, and Celixir shareholder), cardiac surgeon Professor Stephen Westaby (Celixir shareholder) and Professor Sir Martin Evans(Founding Director of Celixir and shareholder from July 2009 to present day). Images of iMPs also appear in a video pitch given by Celixir’s CEO, Ajan Reginald, for an Inspire Wales Science and Technology Award in 2014. The images in the two videos are identical to those that appear in a 2017 publication co-authored by Ina Laura Pieper, who was associated with Celixir from 2010-2013 and is a co-inventor of the PML patent. The 2017 Pieper publication indicates that the ‘iMP’ images used by Celixir in their videos are actually MSCs derived from the peripheral blood (PB-MSCs) of patients in the Morriston Hospital in Swansea who had recently experienced a myocardial infarction. None of the individuals who appear on Celixir’s videos are listed as co-authors on the 2017 Pieper publication.

Moreover, the extensive list of cell surface markers that Celixir’s patent claims iMPs express14, appear to have been obtained from an analysis of PB-MSCs, as evidenced by the fact that Example 2 (HT-FACS analysis) of the iMP patent states the following:

“One vial of cryopreserved PB-MSCs (1×106 cells/ml) was seeded in a T75 cm2 flask containing 15 mL of CTL media (37° C., 5% CO2).”

Of note, the expression levels of surface markers reported in the patent are exactly the same as those in the 2016 publication, despite the fact that PB-MSCs were analysed in the former, and bone marrow-derived iMPs were allegedly analysed in the latter.

This suggests that Celixir’s iMPs are in fact PB-MSCs obtained from patients who were admitted to the Morriston Hospital following an acute myocardial infarction. Consistent with this, the method for isolating PB-MSCs in the Pieper 2017 paper is the same as the method for isolating iMPs in Example 1 of Celixir’s patent [Appendix Table 2].

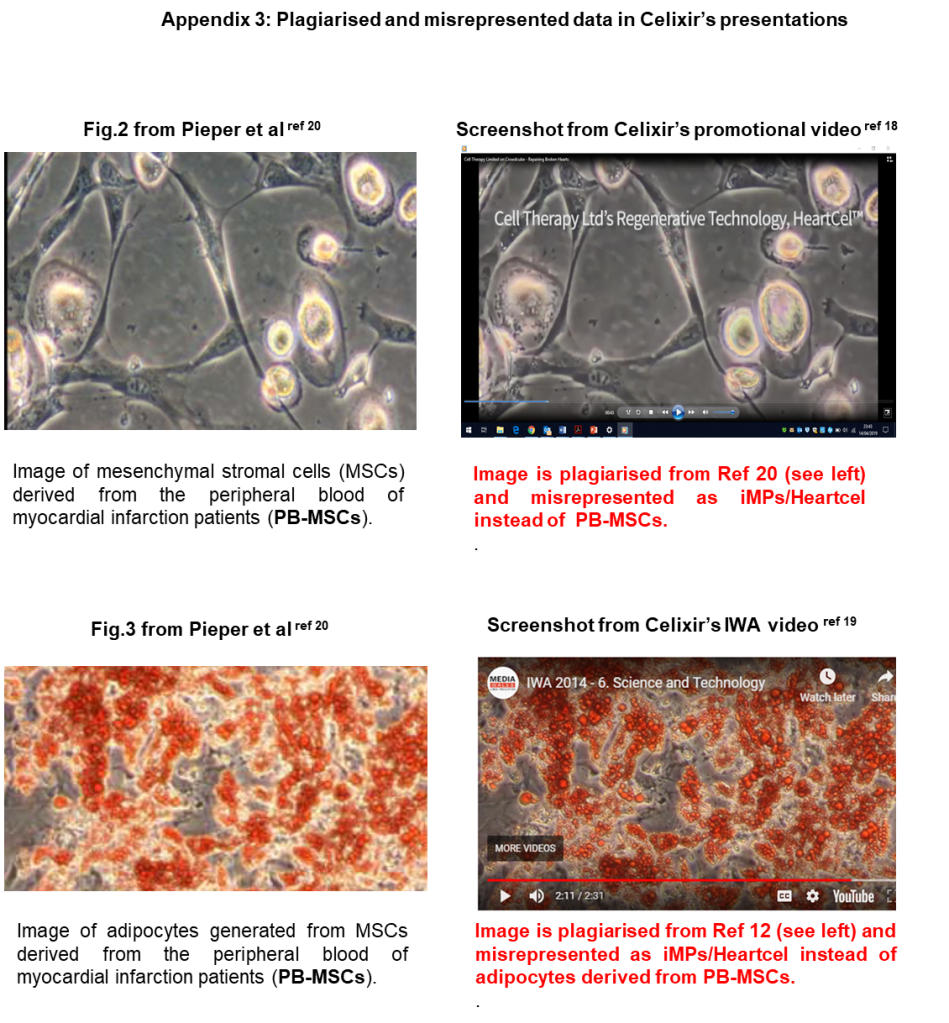

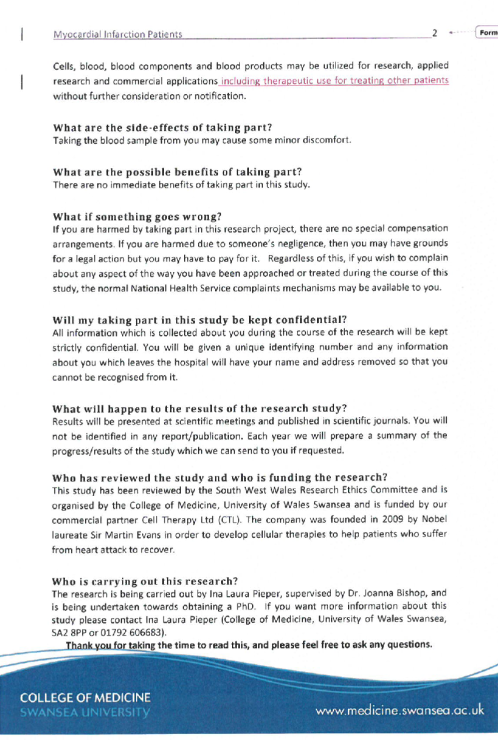

To explore further, FOI requests were sent to NHS Wales and the Health Research Authority (HRA) for copies of Celixir’s application for ethics approval to obtain blood and bone marrow samples from the Morriston patients, along with a copy of the consent form that the patients signed. Celixir’s first application to the REC was made on 14/12/2010, with a proposed start date of 01/03/2011. In this initial application, Celixir indicate they will collect blood from 20 patients admitted to the Morriston Hospital with myocardial infarction, and that the cells derived from these samples will not be used for human application. The research site is listed as the Institute of Life Science, College of Medicine, Swansea University, Singleton Park, Swansea SA2 8PP, and the Principal Investigator can be identified as Ina Laura Pieper.

However, on 17/11/2011, Celixir applied to the REC for a substantial amendment to their project. The key changes included the recruitment of a further 10 myocardial infarction patients to the study, and the following addition (in boldface and underlined) to the patient information sheet:

“Cells, blood, blood components and blood products may be utilized for research, applied research and commercial applications including therapeutic use for treating other patients without further consideration or notification”.

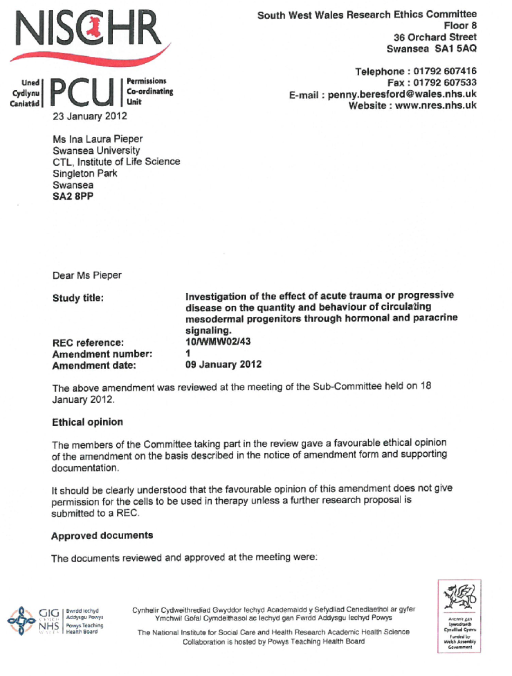

This change to the patient information sheet suggests that at some point between 14/12/2010 and 17/11/2011, Celixir decided that they might like to use the cells derived from the blood of myocardial infarction patients as a therapy in other patients. Celixir received a favourable opinion from the REC on 23/01/12, less than one year before the first patient was recruited to the Greek trial. Importantly, the REC notification stated the following:

“It should be clearly understood that the favourable opinion of this amendment does not give permission for the cells to be used in therapy unless a further research proposal is submitted to a REC.”

It appears that no such proposal was ever submitted by Celixir.

Taken together, it appears that Celixir’s iMPs (aka PMLs) are in fact peripheral blood-derived MSCs (PB-MSCs) obtained from the blood of patients admitted to the Morriston Hospital (Swansea) following an acute myocardial infarction. It seems that Celixir misrepresented the PB-MSCs in a promotional video for potential investors indicating that the company had discovered a unique type of stem cell that could repair damaged heart tissue. The substantial amendment to the REC requesting the change to the patient consent form raises a serious concern that these cells may have been administered to patients who participated in the 2012-2013 Greek trial without REC approval.

2.3 What preclinical tests did Celixir undertake before administering iMPs to patients in Greece?

From the South West Wales REC application, it can be seen that Celixir’s research study using samples from the Morriston patients began on 14/09/2011. According to Clinical Trials.gov, the first patient in the Greek trial was treated with iMPs in November 2012, just 14 months later.

The international publication date for Celixir’s PML patent was January 2013. The only animal data included in this patent is plagiarised and misrepresented (see section 2.1). Apart from some limited flow cytometry data of what appears to be from a single batch of iMPs, the 2016 paper that reports on the 2012-2013 Greek trial contains no characterisation data for iMPs, nor any data to show that they are safe and effective in any animal model. The paper states the cells were quality tested for the following but no results are shown:

“virology (HIV, HTLV-I and II, CMV, EBV, and HCV), mycoplasma (by polymerase chain reaction, PCR), sterility (assessed by gram stain), endotoxin [by the limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) assay], identity (flow cytometry as described above), viability (trypan blue exclusion assay and 7-AAD staining), and karyotyping to exclude chromosomal abnormalities.”

It appears that prior to the 2012-2013 Greek trial, Celixir did not acquire any preclinical safety and efficacy data to show that iMPs (aka PMLs, aka PB-MSCs) were likely to be safe and effective following injection into the myocardium of human patients.

2.4 Were the necessary approvals from the REC, MHRA and Human Tissue Authority (HTA) in place?

REC

From documents released under FOIA by the Health Research Authority (HRA) and NHS Wales (see 2.2), it can be seen that Celixir had REC approval to isolate cells from blood samples obtained from healthy volunteers and from patients at the Morriston Hospital with acute myocardial infarction and chronic liver disease (REC 10/WMW02/43; Principal Investigator, Ina Laura Pieper, Celixir, Swansea University). Celixir could also obtain blood and bone marrow samples from orthopaedic patients via Prof Ian Pallister at the Morriston Hospital (REC 2003.058; Principal Investigator, Prof Ian Pallister, Morriston Hospital).

Both REC approvals allowed Celixir to use cells procured from the patients’ samples for research and commercial purposes. Importantly, Pallister’s application to REC for permission to undertake research using samples from orthopaedic patients did not mention that the cells could be used as therapies in other patients. On the other hand, Pieper’s application specifically indicated that the blood-derived cells could be used for therapeutic purposes (see section 2.2). However, although ethics approval was granted to Pieper, the REC explicitly stated that the cells could not be used therapeutically [see above].

MHRA

Before preparing cells for therapeutic use in a clinical trial in Greece, in compliance with European Commission Directive 2003/94/EC, Celixir should have obtained a manufacturer’s licence from MHRA. This would have required them to demonstrate to the MHRA that they were complying with EU Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP). Although Celixir state in their 2016 publication that the cells were prepared under GMP, there is no evidence to suggest that MHRA-licensed GMP facilities were available at the University of Swansea during the period that the cells were procured (2011-2013). Moreover, from Cell Therapy Limited’s accounts that are publicly available at Companies House, it is clear that the company did not set up GMP facilities until January 2017 [page 30/35, note 23]:

“In January 2017, the manufacturing site of Cell Therapy Hellas was licensed by the Greek Regulator for GMP manufacturing. The Group is now able to manufacture its products under Good Manufacruting Practive, or GMP, which means such products can be used in clinical trials across Europe, the US and Japan, and, once approved by the European regulator for marketing, can be manufactured for sale from this facility across Europe.”

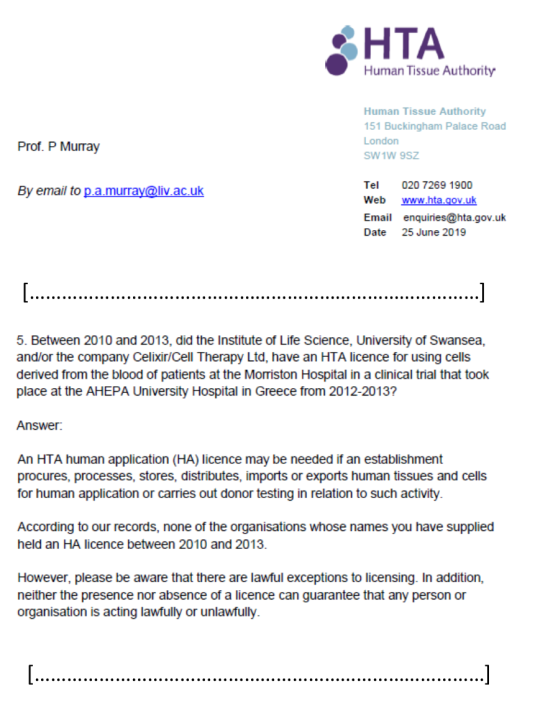

HTA

It would be expected that the procurement, processing, storage, distribution and export of human cells for research purposes or for therapeutic use in patients would require an HTA licence. From information obtained from the HTA under FOIA, it appears that between 2010 and 2013, neither Celixir nor Swansea University held an appropriate HTA licence for the aforementioned activities.

It appears that neither Celixir nor Swansea University had the necessary REC, MHRA or HTA approvals required to prepare cells obtained from patients at the Morriston Hospital for therapeutic use in a clinical trial.

3. Issues relating to trial NCT01753440, undertaken in Greece 2012-2013

The entry on Clinical Trials.gov describes the trial as a “study on safety and efficacy”. However, there was no control group in the study, meaning that all participants received both coronary artery by-pass grafting (CABG) and injection of iMPs into the myocardium. For this reason, it was not possible to claim that the iMPs had any beneficial effects. It would be expected that the patients’ cardiac function would improve because of the CABG.

Despite this, in Celixir’s 2014 promotional video for financial investors, cardiac surgeon and Celixir shareholder, Prof Stephen Westaby, stated the following:

“When we looked 12 months after we injected the cells, what we found was the area of scar had become smaller. Also, the overall contractility of the whole pumping chamber had improved and the patients’ symptoms had got better”.

Westaby failed to mention in the video that the patients had received CABG. The trial results were also presented in overly positive terms in various media reports [here and here].

“This very small study suggests that targeted injection into the heart of carefully prepared cells from a healthy donor during bypass surgery, is safe. It is difficult to be sure that the cells had a beneficial effect because all patients were undergoing bypass surgery at the same time, which would usually improve heart function.”

“A controlled trial with substantially more patients is needed to determine whether injection of these types of cells proves any more effective than previous attempts to improve heart function in this way, which have so far largely failed.”

Indeed, a recent article in the Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA) reports negative results of a Phase 2 trial that similar to Celixir’s 2012-2013 trial, involved injecting mesenchymal precursor cells into the myocardium of patients with heart failure. An editorial comment on the trial stated the following:

“This study is another disappointment for MPCs [mesenchymal precursor cells] in HF [heart failure], especially coming on the heels of the retraction of several stem-cell studies from the laboratory of one disgraced investigator. The lack of evidence hasn’t stopped charlatans from promoting stem cells for HF and other unproven indications”.

The 2016 publication that reported on the 2012-2013 trial that took place at the AHEPA Hospital, Thessaloniki, Greece, states: “The phase IIa safety study was designed to enroll 11 patients”. However, the Clinical Trials entry indicates an intention to recruit 30 patients, raising questions about what happened to the remaining 19 patients. Furthermore, although Celixir claims to have sponsored the Greek trial, and the unique Protocol ID for the trial is ‘AHEPA-CTL-01’, neither Celixir nor Cell Therapy Limited are listed as sponsors in the Clinical Trials.gov entry.

The 2016 publication states:

“iMPs are a novel and distinct mesenchymal precursor cell type discovered and isolated by Cell Therapy Limited, UK (CTL), as a potent cellular therapy intended for cellular therapy in cardiac regeneration. The iMP cells used in this study were prepared under GMP/ISO 9001 conditions.”

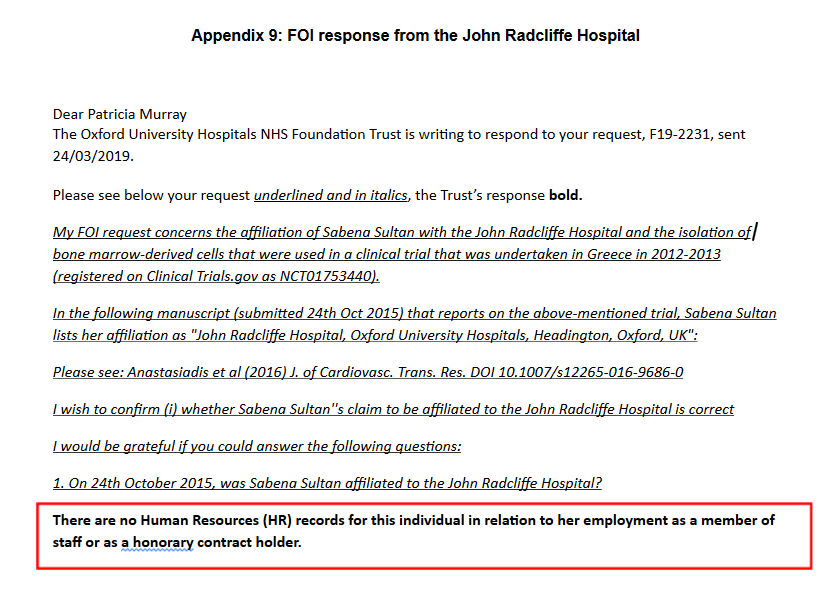

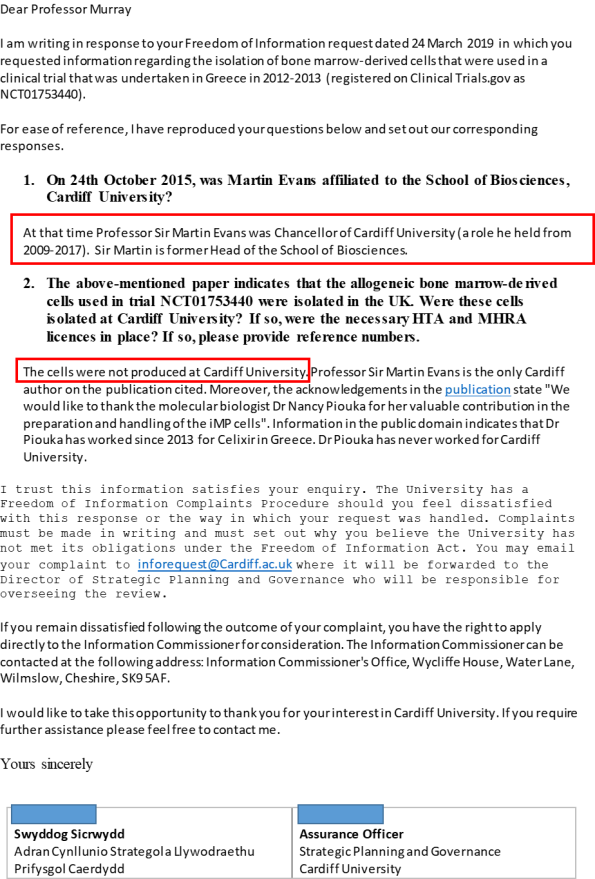

This statement raises questions concerning whereabouts in the UK the iMPs were discovered and isolated? Celixir’s iMP co-inventors, Reginald, Sultan and Evans, are all co-authors of the 2016 publication, but all three appear to have given incorrect affiliations.

For instance, Reginald was not affiliated with the Department of Experimental Therapeutics, University of Oxford; Sultan was not affiliated with the John Radcliffe Hospital; Evans was not affiliated with the School of Biosciences, Cardiff University, havingretired from that position in 2007.

Why didn’t Reginald, Sultan and Evans simply give their correct affiliations? It can be seen from Celixir’s patents and South West Wales REC application that the correct address would have been Cell Therapy Limited, Institute of Life Sciences, Swansea University. In contrast to co-author Westaby, who failed to disclose he had shares in Celixir at the time the Greek trial was conducted, Reginald, Sultan and Evans were quite open about the fact that they were shareholders, which makes the false affiliations all the more puzzling.

As indicated above (section 2.4), there is no evidence that Swansea University had the necessary MHRA and HTA licenses in place to prepare iMPs for therapeutic use. Serious questions are therefore raised concerning the isolation and quality of the cells that were used in the Greek trial. The 2016 paper acknowledges Nancy Piouka “for her valuable contribution in the preparation and handling of the iMP cells”. It is noteworthy that Piouka is not acknowledged for isolating the cells, suggesting that she was only involved in the final stage of cell preparation in Greece. This is described in the paper as follows:

“One week before surgery, the cells were thawed, cultured for approximately 6 days, and harvested using a cell dissociating solution (Sigma Aldrich). The final cell harvest was centrifuged prior to final formulation. The final product was diluted in Isolyte solution at a concentration corresponding to the appropriate dose. The cells were grown to a maximum of three passages before analysis and use.”

Piouka appears to have been employed by both the AHEPA hospital in Greece where the trial was performed, and by Celixir, but was not recruited until after the trial had started, raising questions about who prepared the cells for the first patient.

Another intriguing point regarding the 2016 publication is that it does not cite an earlier trial involving 9 participants that was conducted by the same Greek surgeons at the AHEPA hospital in 2009-2011. This earlier trial was not registered on Clinical Trials.gov, but results were published in 2012. The trial was very similar to the 2012-2013 trial except that autologous bone marrow-derived MSCs were used instead of allogeneic ‘iMPs’. Of note, the 2009-2011 MSC trial reported that the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) increased significantly from 31.3% preoperatively to 52.5% at 12 months. This was actually a greater improvement than in the 2012-2013 iMP trial, which reported an average baseline LVEF of 37.2 % that increased to 48.9% at 12 months.

Why were the results of the 2009-2011 trial not discussed in the 2016 publication, despite the fact that the trials had the same Principal Investigator, Polychronis Antonitsis? Moreover, given that the results obtained with autologous MSCs appeared similar to those allegedly obtained with ‘iMPs’, what was the reason for switching cell types in the forthcoming Brompton trial?

Celixir’s 2012-2013 trial at the AHEPA hospital, Thessaloniki, that aimed to test the safety and efficacy of allogeneic iMPs administered at the time of CABG, had no control arm and should not have been presented in overly positive terms. In the research paper that reported on the trial, Celixir’s Directors, Reginald, Sultan and Evans, gave false affiliations and did not indicate that they were based in Celixir’s premises at Swansea University. A previous trial undertaken at the AHEPA hospital from 2009-2011 that tested autologous MSCs at the time of CABG, was not registered at Clinical Trials.gov and was not cited in Celixir’s 2016 publication, despite the fact that both trials had the same Principal Investigator, Polychronis Antonitsis. The fact that the results from the two trials were similar raises questions regarding the justification for proceeding with allogeneic iMPs rather than autologous MSCs in a larger-scale trial at the Royal Brompton Hospital.

4. Issues relating to the forthcoming trial NCT03515291 at the Royal Brompton Hospital

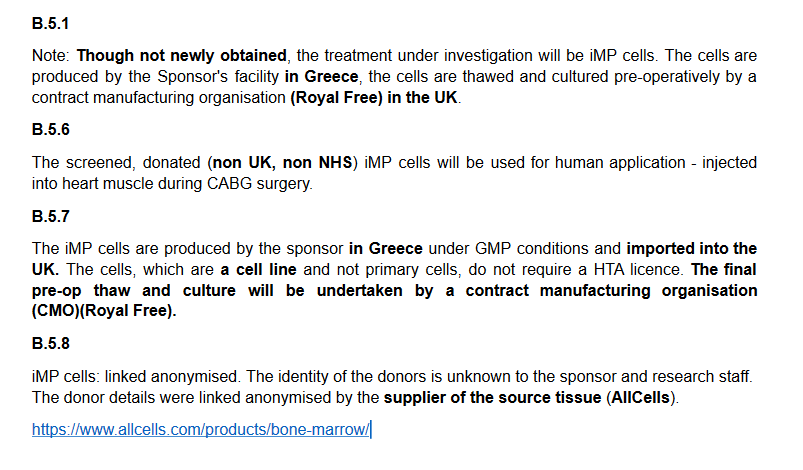

From documents submitted to the Health Research Authority (HRA) by Celixir, it appears that for the Brompton trial, Celixir will obtain either human bone marrow, or human bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells from a company called AllCells in the US [Appendix 11]. These cells will be transported to Celixir’s premises in Greece but it is not clear what will happen to them there. The CEO, Ajan Reginald, has indicated in a presentation given to ‘Intelligent HQ’ in 201734 that the cells may be “modified” to make them “heart-specific” and then “modified” again to make them “very good at reducing scar in the heart.”34 No information is provided as to what these modifications might be. However, it is also possible that the bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells may simply be expanded at the Greek facility and not modified at all. Whether modified or not, the cells will then be transported to a GMP facility at the Royal Free Hospital in London, where they will be cultured again prior to being transported to their final destination at the Brompton, where they will be injected into the myocardium of the trial participants.

A key question here is what will be done to the cells in the Greek facility? And most crucially, why did Celixir set up a GMP facility in Greece in 2017 (see section 2.4, MHRA) to prepare cells for a UK trial? In response to an FOI request, the Royal Brompton Hospital has stated the following:

“The Royal Brompton & Harefield NHS Foundation Trust does not yet have any contract with Cell Therapy Ltd and it has not been confirmed that the Trust will be taking part in the project.”

Although available evidence appears to suggest that the cells used in the 2012-2013 Greek trial were PB-MSCs derived from patients at the Morriston Hospital in Swansea, the cells that Celixir propose to use in the Brompton trial are bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells purchased from a US company. It is not clear why the cells will be processed in Celixir’s GMP facility in Greece rather than in the UK, nor is it clear exactly what processing will be undertaken in Greece.

5. Response of organisations to concerns and FOI requests relating to Celixir’s activities

HRA, NHS WALES, HTA, THE ROYAL BROMPTON HOSPITAL, THE JOHN RADCLIFFE HOSPITAL, OXFORD UNIVERSITY AND CARDIFF UNIVERSITY

These organisations have been cooperative and have responded in a timely manner to FOI requests. The HRA informed me that they were investigating the issues, and on 18th April sent me the following update:

“Please be advised the investigation is still ongoing however the HRA has requested the sponsor place a hold on any recruitment to the study in the interim. No recruitment has taken place as yet.”

MHRA

I alerted MHRA to my concerns regarding the Brompton trial and received the following reply from MHRA’s ‘Enforcement Group’:

“Your email to MHRA has made its way to my team. So I can best proceed, can I ask if you are an employee or ex-employee of Royal Brompton Hospital or affiliated in any employment capacity with them? This is to ascertain whether you meet the agency’s definition of a whistleblower.”

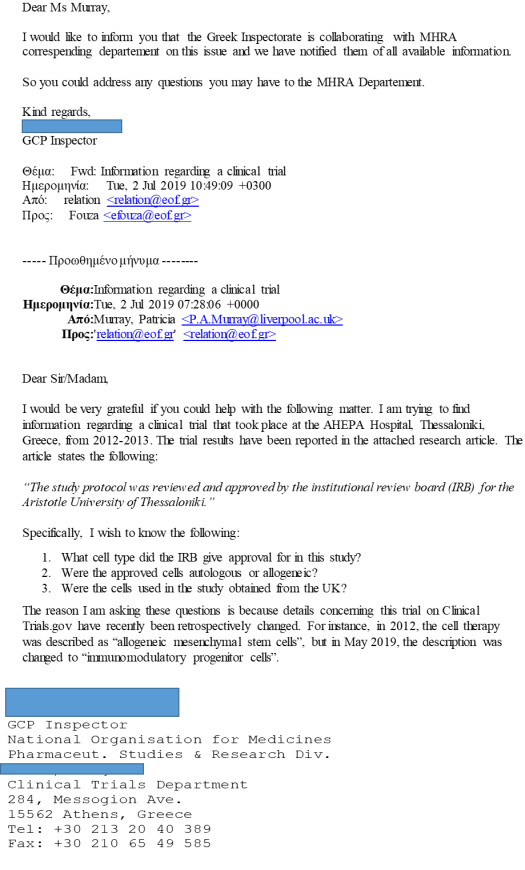

I indicated that I had never been an employee of the Royal Brompton Hospital. I have heard nothing more from the MHRA and don’t know if they have withdrawn the CTA for Celixir’s forthcoming trial. At the time of writing, the trial was still listed on Clinical Trials.gov with the status “not yet recruiting”. However, a message received on 11th July 2019 from the National Organisation for Medicines, Pharmaceutical studies and Research in Greece indicates that MHRA do appear to be investigating the matter.

SWANSEA UNIVERSITY

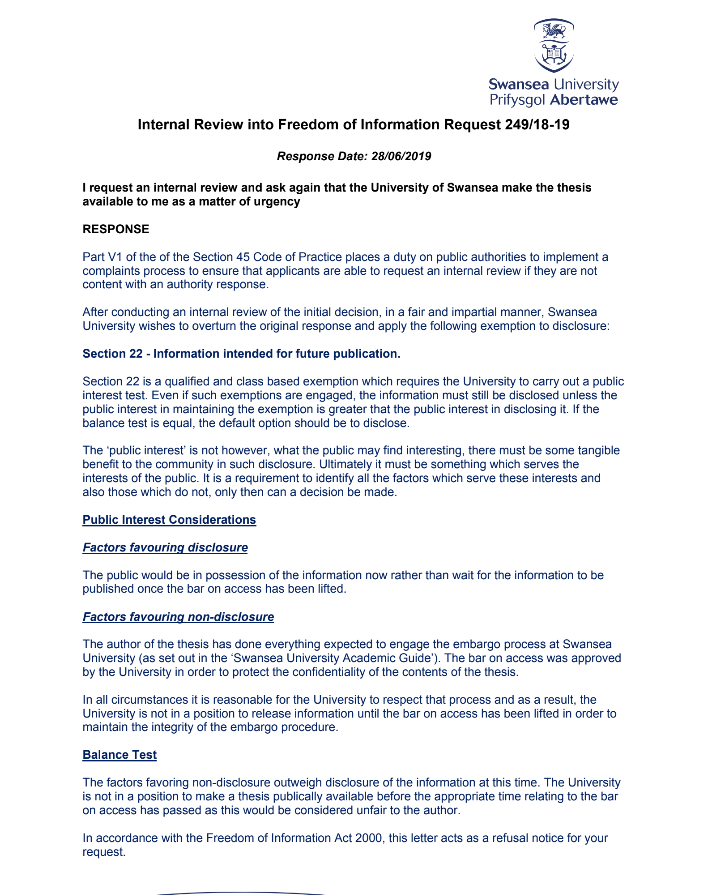

The behaviour of Swansea University has been disappointing. An FOI request was submitted to Swansea on 13/04/19 for access to the PhD thesis of Ina Laura Pieper. The thesis is entitled “Product development of a mesenchymal stem cell therapy for the treatment of myocardial infarction: developing the Enhancell™ product pipeline for Cell Therapy Limited”. The thesis was published in 2014 but is embargoed until April 2020.

Swansea University initially provided incorrect information, indicating that they were refusing the request because the information was available by other means, namely from the National Library of Wales. Swansea University would have known that access via the National Library of Wales were barred until April 2020.

“They [Celixir] also plan to carry out another Phase 2 trial of this product, for Kawasaki disease. Kawasaki disease is an uncommon issue that affects young children, mostly.”

Swansea again refused to make the thesis available. They indicated that they wished to overturn their original response (i.e., that the information was accessible by other means) and instead refused my FOI request on the grounds that disclosure would be “unfair to the author”.

It is worrying that Swansea University has chosen to prioritise the interests of an individual named on a fraudulent patent over the interests of vulnerable patients.

6. Celixir’s subsidiary companies, funders and supporters

6.1 Subsidiary companies

Information available at Companies House indicates that Celixir and Reginald are Directors of 12 other companies, including ‘Cell Therapy Diabetes Ltd’, ‘Cell Therapy Oncology Ltd’, and ‘Cell Therapy Tendoncel’, which underscores the fact that Celixir have ambitions to treat various diseases, ranging from diabetes and cancer to tennis elbow.

The 12 companies are as follows:

- Desktop Genetics Ltd

- Cell Therapy Ltd

- Celixir Innovations Ltd

- Innately Ltd

- Heartcel CABG Ltd

- Cell Therapy Oncology Ltd

- Cell Therapy Skincel Ltd

- Cell Therapy Diabetes Ltd

- SIRNA Ltd

- Cell Therapy Tendoncel Ltd

- Myocardion Ltd

- Bioreactor Corporation Ltd

In May 2019, Reginald set up two new companies called ‘Oncogeni’ and ‘Orthogeni’ where he is sole Director; these are under the name ‘Trevor Ajan Reginald’. The nature of these businesses is listed as ‘research and experimental development on biotechnology’.

As ‘Dr Trevor Ajan Reginald’, he is sole Director of ‘Myocardion’. It is noteworthy that Reginald still appears to be misrepresenting himself as ‘Dr’ here.

There are also several dissolved companies, including ‘ATReginald’ where ‘Trevor Reginald’ was a Director. Of interest, Cell Therapy Ltd’s accounts for year ending July 2016 that are available at Companies House state the following:

“In the period October 2014 to June 2015, Mr Ajan Reginald received consultancy fees through his service company ATReginald Limited. A total of £63,000 (2014: £49,000) was paid to this company.”

The company ATReginald was incorporated in Sept 2012 and was dissolved in Nov 2014 without the above sums appearing on any accounts.

Likewise, ‘Elixir Inventions’ is another dissolved company where ‘Trevor Reginald’ was a Director. Cell Therapy Ltd’s 2017 accounts state the following:

“During the year, Ajan Reginald received £100,000 via his company Elixir InventionsLimited, in exchange for the Company taking full control of all intellectual property invented by Mr Reginald. The Company also paid a total of £83,357 into pensions for Mr Reginald”.

One wonders what IP Reginald invented because this is not specified in the above document. Moreover, it is not possible to see how Elixir Inventions used the £100,000 received for Reginald’s IP, because the company was dissolved before the 2018 accounts were submitted to Companies House.

6.2 Funders and supporters

With the help of their 2014 promotional video, Celixir raised £691,000 from Crowdfunding in just two weeks. The success of this crowd-funded initiative will likely spur on future attempts to obtain more extensive financial backing. Undoubtedly, the appearance on the video of eminent individuals such as the businessman Lord Digby Jones, the renowned cardiac surgeon Prof Stephen Westaby and the Nobel Laureate Prof Sir Martin Evans, would have played a crucial role in the success of the crowdfunding activity, which attracted over 300 investors.

Excerpts from the video are as follows:

Martin Evans:

“I’m Professor Sir Martin Evans and I am very enthusiastic with the possibility of investment through Crowdcube, because what we are working on in Cell Therapy Ltd is the medicine of the future, and really, I think it’s the medicine for everybody, and therefore, crowd sourcing is wonderful. It’s a medicine for you.”

Digby Jones:

“And so there you have it. You’ve heard from a Nobel Laureate, you’ve heard from a professor of heart surgery [Stephen Westaby]. I’m no scientist, but I’m a businessman, and perhaps you can see now why I personally have invested in Cell Therapy Ltd.”

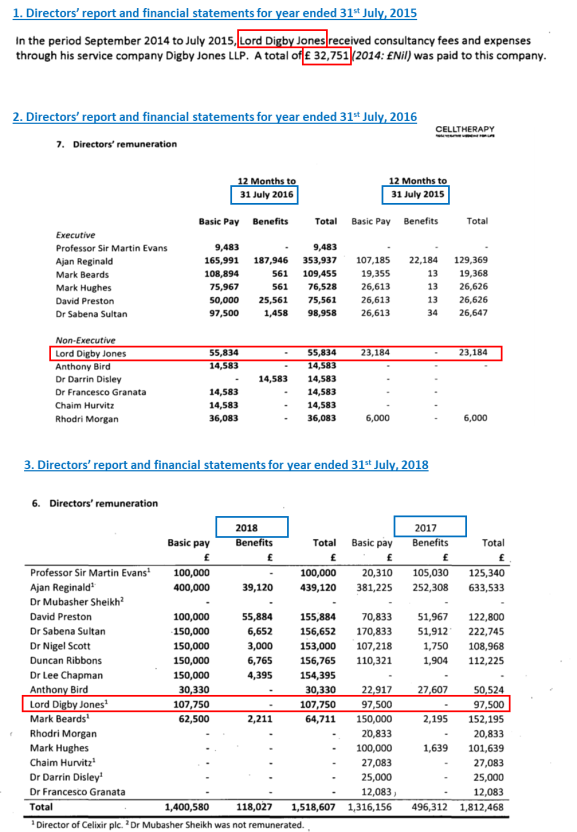

Until January 2018, Jones served as a Director for Cell Therapy Limited and was handsomely remunerated:

Celixir/Cell Therapy Limited have also been previously supported by the late Rhodri Morgan MP, former First Minister of Wales, and Helen Grant MP, who both served as Directors and were shareholders.

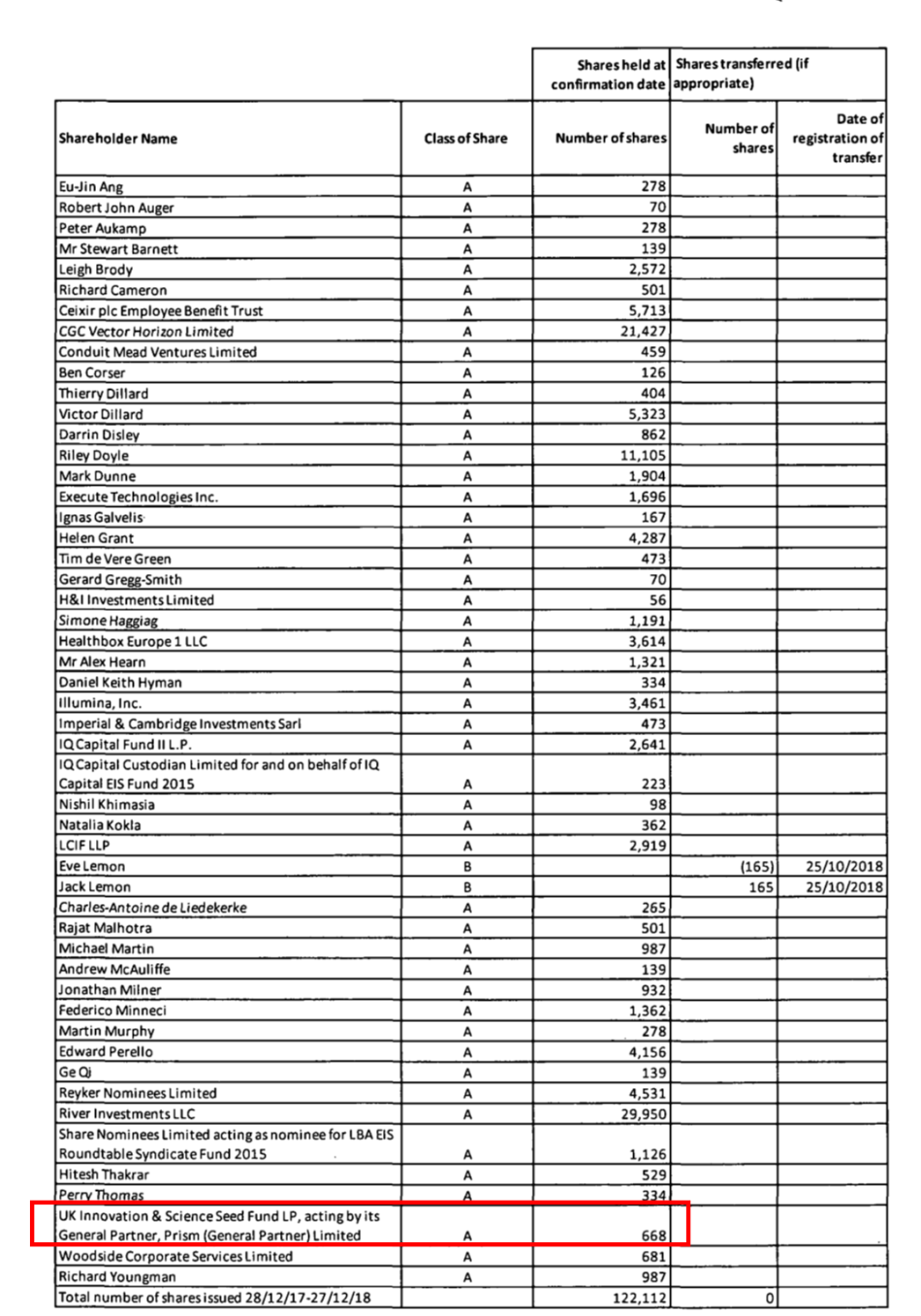

A confirmation statement indicating new shareholders that was submitted this year to Companies House by Celixir indicates that the UK Innovation and Science Seed Fund is now a Celixir shareholder. The UK Innovation and Science Seed Fund is backed by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, so it appears that public money is now being invested in a fraudulent company.

7. Conclusion

Hopefully, now that the concerning issues relating to Celixir’s forthcoming trial at the Royal Brompton Hospital have come to light, the MHRA will withdraw the Clinical Trials Authorisation (CTA). However, it is quite worrying that the CTA was ever granted in the first place. The MHRA’s role is to protect and improve public health and ensure that medicines meet applicable standards of safety, quality and efficacy. In the case of Celixir, it appears that the MHRA failed to execute appropriate due diligence. At the very least, the MHRA should have checked that the cell type listed on the Clinical Trials entry for the 2012-2013 Greek trial was the same cell type that Celixir were proposing to use in the Brompton trial. A potential problem here is that another of MHRA’s roles is to ‘enable innovation’ and there is a risk that a desire to help companies bring innovative products to patients might sometimes conflict with ensuring those innovations meet applicable standards. However, even if the MHRA had refused to grant Celixir the CTA, this company would still pose a risk to vulnerable patients and the general public, including financial investors. Unfortunately, there is no single organisation for dealing with the range of questionable activities that Celixir have been engaging it, making it very difficult to hold them to account and take appropriate action to protect the public.

Acknowledgement

Dr Leonid Schneider (For Better Science Blog), Elizabeth Woeckner (Citizens for Responsible Care & Research) together with several other scientists and clinicians are thanked for their invaluable assistance.

Our Editor Phil Parry’s memories of his extraordinary 35-year award-winning career in journalism as he was gripped by the incurable disabling condition Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in a major new book ‘A GOOD STORY’. Order the book now!

Our Editor Phil Parry’s memories of his extraordinary 35-year award-winning career in journalism as he was gripped by the incurable disabling condition Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in a major new book ‘A GOOD STORY’. Order the book now!