- Wordy again part three - 16th February 2026

- ‘Lies, damned lies etc…’ - 13th February 2026

- Missing in action - 12th February 2026

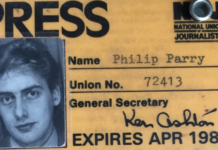

During 23 years with the BBC, and a 41 year journalistic career (when he was trained to use clear and simple language, avoiding jargon), our Editor, Welshman Phil Parry has always been lucky enough to work in a largely free environment and continues to do so now with The Eye, but others do not which is emphasised today by a ‘freedom of expression’ award to a Russian human rights activist.

I’m lucky – I have never been put behind bars or (successfully) sued for what I have published.

Others, though, are less fortunate and I salute them. One such is Evgenia Kara-Murza a Russian human rights activist, who, the Index on Censorship has announced in London, is the winner of the 2024 Freedom of Expression Trustee Award. She is Advocacy Director of the Free Russia Foundation and wife of the political prisoner Vladimir Kara-Murza, who was poisoned and then imprisoned on April 11 2022 for protesting about Russia’s war in Ukraine.

As a result of Ms Kara-Murza’s tireless campaigning, her husband was finally released from prison in the Summer as part of a prisoner exchange deal.

Apparently endorsing this there are fine words by governments and organisations (mainly in the west) about the importance of media freedom, and allowing journalists to do their work unhindered, but the reality is rather different.

For instance, in the UK Government’s National Action Plan for the Safety of Journalists, last October, it was announced: “Journalism in the United Kingdom has a long and proud history. Since the days of John Wilkes, journalists have never shied away from holding the powerful to account – and in so doing, their work has shaped our society. Underneath this lies a fundamental principle: that a journalist, whatever their persuasion, can do their job to the best of their ability, without fear or favour. Unfortunately, too many journalists working in the UK today can no longer take that right for granted, and are facing both abuse and threats to their personal safety as well as encroachments on their freedom of expression.”

For instance, in the UK Government’s National Action Plan for the Safety of Journalists, last October, it was announced: “Journalism in the United Kingdom has a long and proud history. Since the days of John Wilkes, journalists have never shied away from holding the powerful to account – and in so doing, their work has shaped our society. Underneath this lies a fundamental principle: that a journalist, whatever their persuasion, can do their job to the best of their ability, without fear or favour. Unfortunately, too many journalists working in the UK today can no longer take that right for granted, and are facing both abuse and threats to their personal safety as well as encroachments on their freedom of expression.”

Sadly one journalist working in the UK knows the truth about this last bit more than most of us. The Chief Reporter for the Mail, the local newspaper at Barrow-in-Furness in Cumbria, Amy Fenton, was forced to flee her home after receiving a torrent of insults and threats, when she reported a local court case. Police said there was a “credible risk to her life and that of her child”.

In other parts of the world it is even worse. According to the World Press Freedom Index (WPFI) 2023 – which evaluates the environment for journalism in 180 countries or territories, and is published on World Press Freedom Day (WPFD) (May 3)) – the situation was “very serious” in 31 countries, “difficult” in 42, “problematic” in 55, and “good” or “satisfactory” in only 52 countries. In other words, the environment for journalism was ‘bad’ in seven out of 10 countries.

In other parts of the world it is even worse. According to the World Press Freedom Index (WPFI) 2023 – which evaluates the environment for journalism in 180 countries or territories, and is published on World Press Freedom Day (WPFD) (May 3)) – the situation was “very serious” in 31 countries, “difficult” in 42, “problematic” in 55, and “good” or “satisfactory” in only 52 countries. In other words, the environment for journalism was ‘bad’ in seven out of 10 countries.

Norway was ranked first for the seventh year running, with Ireland second, and Denmark third. The last three places were occupied solely by Asian states with North Korea at the bottom of 180 countries.

But in Europe too there is cause for concern. After Slovenia seceded from Yugoslavia in 1991, it gave Radio Television of Slovenia (RTV-SLO) a mandate to report independently, unlike the state propaganda that passed for news under communism. Yet the Government there refused to pay RTV-SLO’s budget, and wanted to pass a new media law that would make it easier to control.

In Latvia, the chief risk is the legal and financing structure. The country’s new public-media law failed to include a set-aside tax, like the television licence fee that funds the BBC (which could now be cut after the Martin Bashir affair), and that leaves it vulnerable to political pressure, while it is not clear that the supervisory board will be protected from political appointments.

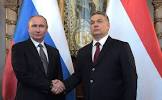

Meanwhile when Viktor Orban won power in Hungary in 2010 he adapted Vladmir Putin’s blueprint, transforming the state media agency MTVA into a propaganda organ. The group was restructured into a shell company in a fashion that exempted it from the law governing public media, and during the European Parliament (EP) elections in 2019, editors at MTVA were recorded instructing reporters to favour Mr Orban’s Fidesz party.

Meanwhile when Viktor Orban won power in Hungary in 2010 he adapted Vladmir Putin’s blueprint, transforming the state media agency MTVA into a propaganda organ. The group was restructured into a shell company in a fashion that exempted it from the law governing public media, and during the European Parliament (EP) elections in 2019, editors at MTVA were recorded instructing reporters to favour Mr Orban’s Fidesz party.

Poland’s Law and Justice (PLS) party followed Mr Orban’s example when it won power in 2015, and quickly turned TVP, the public television network, into a bullhorn for the party.

The network championed campaigns against gay rights and demonised the opposition mayor of Gdansk. After he was assassinated by an extremist in 2019, a court told TVP to pay damages, but it did not comply.

However outside the EU, the problems facing an independent media are even worse.

The prime example, of course, is Russia where RT (Russia Today) is accused of being a mouthpiece for the Kremlin. By the mid-2000s Russian news shows’ agendas were being set at government-led meetings.

The prime example, of course, is Russia where RT (Russia Today) is accused of being a mouthpiece for the Kremlin. By the mid-2000s Russian news shows’ agendas were being set at government-led meetings.

Mr Putin signed a law that will allow Russia to declare journalists and bloggers “foreign agents” in a move that critics say will allow the Kremlin to target government critics.

Under the vaguely worded law, Russians and foreigners who work with the media or distribute their content and receive money from abroad would become ‘enemies of the state’, potentially exposing journalists, their sources, or even those who share material on social networks to foreign agent status.

In Belarus the situation is also appalling. At least 16 journalists there are behind bars, and riot police are singling out reporters for arrests and beatings at protests as the media is intimidated.

The dictator there Alexander Lukashenko, forced a Ryanair passenger plane to make an unscheduled stop in his capital in order to arrest the editor of an internet channel, NEXTA, that has been reporting on his crackdown.

Roman Protasevich was taken off the plane, which was flying from Athens to Vilnius, the Lithuanian capital.

Citing what it said was ‘evidence’ that there were explosives on board, the authorities forced the aircraft to land in Minsk as it passed through Belarusian airspace on its way to neighbouring Lithuania, sending a MiG fighter plane to escort the Ryanair jet down. The state news agency later reported that no explosives had been found, and it seems certain that the incident was invented purely as a way of arresting the journalist.

The alarming details came after Marina Zolotova, the editor of Tut.by, an independent news website in the counrry, said: “Blue press jackets and press badges have become targets. When journalists go to cover a protest they cannot be sure that they will come home. This is a real war by the authorities against independent journalism and their own people.”

It is clear that Mr Lukashenko is waging a war against journalists who have dared to report on his regime’s brutal crackdown against peaceful protesters.

At least eight protesters have been killed and hundreds more have alleged torture and rape, in police custody.

Among the most high-profile of those in prison is Ekaterina Bakhvalova, who was arrested as she filmed riot police firing stun grenades into a crowd demonstrating against the death in police custody of a fellow protesters.

Several years ago Ms Bakhvlova was sentenced to an additional eight years in prison for “state treason”, when she had already been serving a two-year sentence for “violating public order”.

These sort of ridiculous charges are what people like her face when they report the truth.

As Ms Kara-Murza knows only too well…

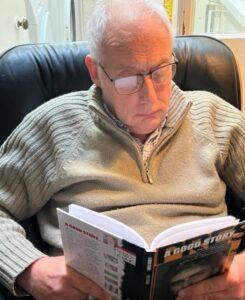

The memories of Phil’s extraordinary decades long award-winning career in journalism (including significant events like these) as he was gripped by the rare neurological disabling condition Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in a major book ‘A Good Story’. Order it now.