- History man - 3rd March 2026

- British Broadcasting Complaint (BBC) - 3rd March 2026

- Rocket man - 2nd March 2026

On The Eye our Editor Phil Parry has described how he was helped to break into the South Wales Echo office car when he was a cub reporter, recalled his early career as a journalist, the importance of experience in the job, and making clear that the ‘calls’ to emergency services as well as court cases are central to any media operation.

He has also explored how poorly paid most journalism is when trainee reporters had to live in squalid flats, the vital role of expenses, and about one of his most important stories on the now-scrapped 53 year-old BBC Wales TV Current Affairs series, Week In Week Out (WIWO), which won an award even after it was axed, long after his career really took off.

Phil has explained too how crucial it is actually to speak to people, the virtue of speed as well as accuracy, why knowledge of ‘history’ is vital, how certain material was removed from TV Current Affairs programmes when secret cameras had to be used, and some of those he has interviewed.

After disclosing why investigative journalism is required now more than ever although others have different views, here he examines why poverty is so difficult to eradicate and some of the extremely deprived areas where he has conducted journalist interviews.

We always said they were ‘rough’ places.

Looking back though, it was clear that the people didn’t actually WANT to live like they did, or in the areas they were placed.

Poverty was often the driving force.

On the now-defunct BBC Wales television current affairs programme Week In, Week Out (WIWO) I have filmed in countless homes of poorer people, and they always had a particular smell.

The houses smelt exactly the same way – a combination of dirty carpets, cheap cigarettes, and damp.

On one extremely deprived estate in South Wales when I went to see a family for the network BBC TV programme Panorama there were spikes on the top of poles which were surmounted by strategically-placed CCTV cameras.

In another, filming for a different Panorama in Manchester, we kept having to stop the interview so the woman we were talking to could go to the kitchen door to conduct her drug deals.

But the roughest place I ever filmed in was at Nottingham for the also now-axed BBC TV programme Public Eye.

In the kitchen where we were filming there wasn’t actually a door, cardboard had been placed over the gap!

And dogs, there were always large dogs.

In many of the houses where I filmed, the gardens were full of dog faeces.

Meanwhile the figures show that things are better than they once were for poorer people, but there is still a long way to go.

More than four million people in the UK are trapped in deep poverty, meaning their income is at least 50 per cent below the official breadline, locking them into a weekly struggle to afford the most basic living essentials.

Seven million people, including 2.3 million children, are affected by ‘persistent poverty’, meaning that they were not only in poverty but had been for at least two of the previous three years.

Another study found that of 14.3 million in the UK in poverty, 4.5 million were in deep poverty – a third of all those were also on the breadline.

In cash terms this meant that a couple with two children would have an income of less than £211 a week after housing costs, while a single parent with one child would be on under £101.50 a week.

In recent years there has been a dramatic rise in child poverty in families with three or more children – it has risen by nine percentage points since 2013-14.

Disability is one of the strongest predictors of being in poverty, with nearly half of all those living below the breadline in a household where someone is disabled.

Work is no longer a guarantee of protection against poverty either.

At the millennium 54 per cent of children in poverty lived in a family where an adult worked, and that rose to 73 per cent in 2017-18.

Even in families where all adults work full time, one in six children are in poverty.

Across the world, the picture is no less bleak, although great strides have been made.

In 2015, 10 per cent of the world’s population still lived on less than US $1.90 a day, but this was down one per cent in two years.

It is also obvious from the figures that progress has been uneven:

- In two regions, East Asia and the Pacific, 47 million are classified as ‘extreme poor’, and in Europe and Central Asia 7 million are ‘extreme poor’.

- More than half of the ‘extreme poor’ live in Sub-Saharan Africa. In fact, the number of poor in the region increased by nine million, with 413 million people living on less than US $1.90 a day in 2015, and this was more than all the other regions combined. If the trend continues, by 2030, nearly 9 out of 10 ‘extreme poor’ will be in Sub-Saharan Africa.

- The majority of the global poor live in rural areas, are poorly educated, employed in the agricultural sector, and are under 18 years of age.

So they aren’t just ‘rough’ areas – they are also extremely poor ones.

So they aren’t just ‘rough’ areas – they are also extremely poor ones.

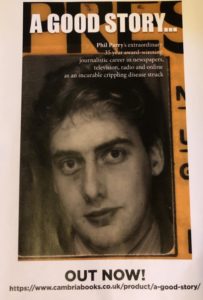

Phil’s memories of his extraordinary 36-year award-winning career in journalism as he was gripped by the incurable disabling condition Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in a major new book ‘A GOOD STORY’. Order the book now! The picture doubles as a cut-and-paste poster!