- Ewe turn - 10th February 2026

- Church times - 9th February 2026

- Up, up and away… - 6th February 2026

Here our Editor Phil Parry examines the concept of ‘nationhood’, as the idea is promoted tirelessly today and the death of Prince Philip puts it centre stage, with Wales among the countries playing a lead role.

Earlier he described how he was helped to break into the South Wales Echo office car when he was a cub reporter, recalled his early career as a journalist, the importance of experience in the job, and making clear that the ‘calls’ to emergency services as well as court cases are central to any media operation.

He has also explored how poorly paid most journalism is when trainee reporters had to live in squalid flats, the vital role of expenses, and about one of his most important stories on the now-scrapped 53 year-old BBC Wales TV Current Affairs series, Week In Week Out (WIWO), which won an award even after it was axed, long after his career really took off.

Phil has explained too how crucial it is actually to speak to people, the virtue of speed as well as accuracy, why knowledge of ‘history’ is vital, how certain material was removed from TV Current Affairs programmes when secret cameras had to be used, and some of those he has interviewed.

He has disclosed as well why investigative journalism is needed now more than ever although others have different opinions, how the current coronavirus (Covid-19) lockdown is playing havoc with media schedules, and the importance of the hugely lower average age of some political leaders compared with when he started reporting.

OK, I’m going to do it.

I am entering shark-infested waters, and will look at the concept of ‘nationhood’.

I expect to be attacked by those who support the idea of a ‘nation’ (not least by people in Wales) and by those who are against it.

Nationalism is on people’s lips once more and yet, in the wrong hands, it can be the most disruptive force in politics.

I hesitate to say ‘more than ever’ because there have historically been huge upsurges in nationalism – notably in the 19th century.

The difficulties are obvious.

My dad (who fought against extreme nationalism in the Second World War and saw the ugly side of it during the 1930s) said many years ago that he couldn’t understand why nationalism was bad when it’s big, but good when it’s small.

I am still struggling with this conundrum today. I used to square the circle by giving the traditional response, that if a fight against a bigger, more powerful oppressor expressed itself as nationalism, then it was good, otherwise it was bad.

Now I’m not so sure. Perhaps he was right, and ALL nationalism is bad!

The whole business is muddled – there is, TECHNICALLY, no British ‘nation’, just those of England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland (if indeed that is a ‘nation’ at all!), making up the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, unless you believe one was forged out of its controversial imperial past.

It’s RELATIVELY recent too – only created in 1921 after what became the Republic of Ireland was hived off.

So when Leo Amery was urged to “speak for England” in the House of Commons in 1940, strongly implying Neville Chamberlain wasn’t doing so, he was, of course, being urged to do it actually for the ‘UK’, for which the word seems to have been used as a synonym.

The entire bizarre concept has been thrown into sharp relief for me by the death on Friday of Prince Philip at the age of 99, and the extraordinary amount of coverage devoted to it, which has been heavily criticised by the public.

A message on The BBC website read: “We’re receiving complaints about too much TV coverage of the death of HRH Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh”, and officials created a dedicated complaints page on the website.

Over the last few days, the word ‘nation’ has been bandied around willy-nilly.

In an interview by Prince Andrew (the first since his disastrous one in 2019) his father was described as “the Grandfather of THE NATION”.

The English one presumably?

The BBC’s Royal Correspondent Nicholas Witchell, said it was “a moment of real NATIONAL sadness”.

Yet which of the UK’s ‘nations’ was it a ‘moment’ of sadness for?!

Sky’s headline was: “Prince Philip: What does it mean to be in a period of NATIONAL mourning?”.

What indeed?!

Even Boris Johnson seems confused, and when talking about the minute’s silence to mark a year of lockdown on March 23, along with those who have died in the pandemic, he said: “We should also remember the great spirit shown by our NATION over this past year”.

But which ‘nation’s’ spirit should we remember? Surely such an intelligent man can’t believe there’s a British one?!

Meanwhile a great deal of attention has been focused on Scotland, and whether this ‘nation’ might break away from the union, followed, perhaps, by Wales (although this seems unlikely).

Yet the English ‘nation’ is coming to the fore now too.

It has always seemed strange to me that God Save the Queen is sung by English sports fans as their anthem, because, it appears, there is no equivalent one for England.

Some will also dress up as Norman knights during a match, to show their support for the English team, despite the fact that Normandy is, er, in France!

But in 2015, for the first time in history, and twice thereafter, FOUR different parties (representing the full gamut of views, from strong opposition to nationalism, to backing for it) topped the polls in the UK’s FOUR different territories.

‘Englishness’, a new book by Ailsa Henderson and (Welshman) Richard Wyn Jones, though, is not muddled – it is a scholarly testimony to the union’s strengths.

The nine big quantitative surveys of ‘Englishness’ they have conducted since 2011 demonstrate that the number of people who describe themselves as exclusively or mainly ‘English’ rather than ‘British’ is growing, and that the idea of ‘Britishness’ – once the glue that held the UK together – is splintering.

Londoners use ‘British’ to signal their cosmopolitanism; the Scots and Welsh to signal their unionism.

The 2014 Scottish referendum stoked English grievances without satisfying the Scots, and the 2015 election turned a growing political division between the two (along with Wales) into a chasm, which was only made deeper when Mr Johnson was elected in 2019.

Many in England apparently feel that by pocketing more money than they create, the Scots and Welsh are not playing fair (for example Scottish Government funding per person is 31 per cent above English levels, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies), and that membership of the EU was wrong because Parliament is the only legitimate source of power, while English history has provided ‘our island nation’ with both a web of ties with the Anglo-sphere and a unique global economic and strategic niche.

But the idea of Britain as an ‘island’ is also problematic.

But the idea of Britain as an ‘island’ is also problematic.

The historian Norman Davies called his book exploring nationhood ‘The Isles’ for that very reason.

One of the difficulties with English nationalism, in its newly radicalised and politicised form, is that it may be too big to be tamed, England accounts for 84 per cent of the British population (and growing) while Greater London has more people than Scotland and Wales combined.

This is a situation which is very different from Germany or the USA where no lander or state carries such a crushing weight among its peers.

The building of the UK was, over a millennium, the story of England’s relentless (at times extremely brutal), expansion. First riding roughshod over the Celtic lands on its borders, then peoples across the world. The 1707 Act of Union brought Scotland and England ‘together’ yet was strongly resisted north of the border. A ‘union of crowns’, when James VI of Scotland also became James I of England, in 1603, was a kind of precursor.

Empire building is usually a pretty savage affair and this was no exception with England‘s, then Britain’s, success in carving out a world empire from the 17th century onwards, giving every UK ‘nation’ a stake in the shared prosperity.

It isn’t only Britain either, where the concept of the nation-state appears to be in the ascendancy.

In France for example (which has a greater claim than most countries to being a long-unified state and nation, although its boundaries changed radically in the 20th century) the idea of what is, and what is not, ‘FRENCH’, is likely to become a major issue in the forthcoming Presidential election.

Marine Le Pen leader of the (renamed) National Rally has long emphasised the French ‘nation’ while her rival Emmanuel Macron appears to be abandoning some of his post-national globalist policies.

A ‘republican values’ bill introduced by Mr Macron, which his critics see as a hunt for Ms Le Pen’s far-right vote, is also designed to curb Islamism in the French ‘nation’.

But the phrase ‘the nation’ was even used in reports of how the public complained strongly about the amount of coverage concerning Prince Philip’s death.

Viewers switched off their television sets in droves after broadcasters aired blanket coverage of his death, and The BBC received so many complaints it created the dedicated complaints form on its website.

BBC One and BBC Two cleared their schedules of Friday night staples including EastEnders, Gardeners’ World and the final of MasterChef, to simulcast pre-recorded tributes from the Duke of Edinburgh’s children.

There is, though, an underwhelming appetite for abandoning altogether the idea that the UK is an exceptional ‘nation’ – and it is illustrated extremely well by Mr Johnson’s minute’s silence statement, and in the tributes now to Prince Philip (the Daily Mail for instance, offered 144 pages, with that newspaper having an average daily readership of over two million people last year!).

In 1908 G.K. Chesterton wrote a poem called ‘THE SECRET PEOPLE’ which included the refrain “we are the people of England that never have spoken yet”, and now that some of the people of England have started speaking they are not going to be silenced soon.

Perhaps they might want to go back to the days of ‘for Wales see England’…

Perhaps they might want to go back to the days of ‘for Wales see England’…

Tomorrow – disturbing exclusive revelations on The Eye about a controversial WELSH university.

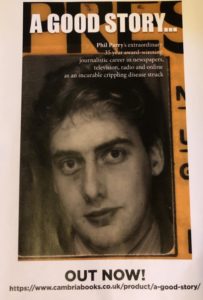

Welshman (although on the border with England!) Phil’s memories of his remarkable decades long award-winning career in journalism as he was gripped by the rare disabling condition Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in a major book ‘A GOOD STORY’. Order the book now!