- Return to sender - 20th February 2026

- Legal eagle - 19th February 2026

- Round Robin - 19th February 2026

As the General Election (GE) nears, it becomes increasingly obvious that private schooling will become a key political battle ground, with Labour pledging to remove some tax reliefs, so here our Editor Welshman Phil Parry (who attended an independent school in Wales), looks at the issues involved.

Earlier he described how he was helped to break into the South Wales Echo office car when he was a cub reporter, recalled his early career as a journalist, the importance of experience in the job, and making clear that the ‘calls’ to emergency services as well as court cases are central to any media operation.

He has also explored how poorly paid most journalism is when trainee reporters had to live in squalid flats, the vital role of expenses, and about one of his most important stories on the now-scrapped 53 year-old BBC CW series he presented for 10 years, Week In Week Out (WIWO), which won an award even after it was axed, long after his career really took off.

He has also explored how poorly paid most journalism is when trainee reporters had to live in squalid flats, the vital role of expenses, and about one of his most important stories on the now-scrapped 53 year-old BBC CW series he presented for 10 years, Week In Week Out (WIWO), which won an award even after it was axed, long after his career really took off.

Phil has explained too how crucial it is actually to speak to people, the virtue of speed as well as accuracy, why knowledge of ‘history’ is vital, how certain material was removed from TV Current Affairs programmes when secret cameras had to be used, and some of those he has interviewed.

He has also disclosed why investigative journalism is needed now more than ever although others have different opinions, and how information from trusted sources is crucial at this time of crisis.

Perhaps it should be part of the curriculum. It could be on the timetable as: ‘A politics lesson’.

It has become obvious that education policy (which is devolved in Wales where Labour are in charge), will be a critical battleground for politicians at the next General Election (GE) – particularly private (confusingly also called ‘public’) schools.

For decades, on and off, the Labour Party have been promising to take a harder line on private, fee-paying schools.

For example, before the GE in 2019 they pledged to explore ways of “integrating” them into the state sector. That idea has been dropped, along with one to strip private schools of their charitable status which has always been anomalous.

The winning argument against this was that it would drive up fees. My answer to that has always been; ‘so what?!’ (as someone who went to a private school, I lay claim to having an opinion on this).

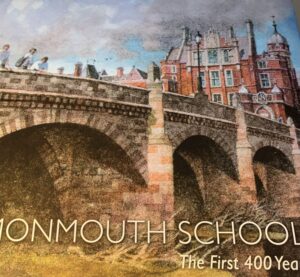

But the policies which were spelled out to enthusiastic applause at Labour’s conference this year – to make private-school fees subject to Value Added Tax (VAT), at the standard rate of 20 per cent, and to remove a discount these schools receive on business rates – are only slightly less problematic for independents. Given the party’s yawning lead in the polls, they may well also become reality at a Uk level, it seems relevant then, to examine the future as well as past of these schools, in the context of the one I went to, Monmouth School.

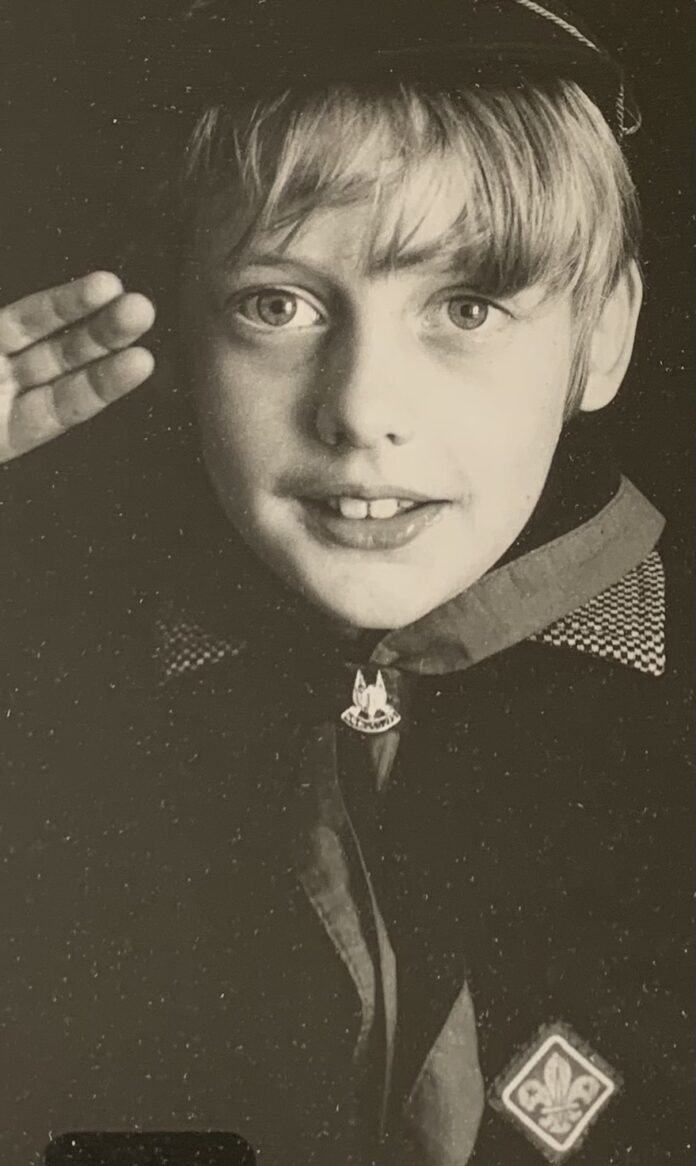

I attended Monmouth School (a second division private school and certainly not in the league of Eton or Marlborough), between 1973 and 1980 on a ‘direct grant’, and the education was excellent, if extremely traditional. There were, however, controversies.

I never suffered any direct sexual abuse, although I clearly remember being instructed (with others) to take down my shorts by the (now dead) rugby master, so that he could check whether I was wearing a jock strap or trunks and not underpants before a game. Even at 11 I thought this was a bit odd…

Beatings were commonplace, and I recall well being hit in the head by one master we called ‘Bill Griff’ (also now dead) because, along with the rest of the class, I was ‘marching’ into his Chemistry lesson and making a noise on the wooden floor.

This teacher was housemaster, as well, of the small boys’ boarding house called St James’, where the children went before they were assigned to their allotted senior houses. He hit boys there too. A young friend of mine who was at St James’, confided in me that this master had told him although he caned other boys, he would not touch him because he liked him. These were children of 11 or 12.

A class vote before the beatings happened on occasions (I was always getting beaten for day dreaming or talking in class) and when I was the subject of one once, everyone voted for me to be ‘dapped’ except, to his eternal credit, my best friend at the time (a ‘dap’ is known as a ‘plimsoll’ or ‘trainer’ to some).

A biology teacher used to beat boys on their behinds using a large pair of wooden protractors with the word ‘IDIOT’ scrawled on the instrument backwards in chalk. After the beating took place the victim would have ‘IDIOT’ in chalk the right way round on his backside.

On another occasion when I was misbehaving in the dinner queue, a master came up behind me, hurled me down a flight of stone stairs and held me up against a wall. I was only 12.

Before a caning on the hand the Headmaster Robert Glover (who was described as “the last of the emperors” in a recent book by the school), would often say: “Why have you got your hands in your pockets boy? If they’re cold, I’ve got a way of warming them up for you!”.

But these assaults had an appalling effect on us as children, which lasted until we were adults. My best mate in school (the one who voted for me not to be ‘dapped’) only told me a few years ago of how he was caned by the Headmaster for riding his bike in the wrong part of school. He was in his 50s.

He found the experience painful, and so deeply humiliating he did not tell me at the time nor for years afterwards, yet I have seen him countless times since we both left Monmouth School.

Another master used to keep an old ‘dap’ in his bag to hit the boys if they misbehaved. Before the beating took place he would often ask for a class vote on whether the ‘dap’ should be used and, of course, boys being boys, they invariably voted for the assault to take place.

In response to publication of these kind of memories on The Eye, I was contacted by another pupil, who also attended the school in the 70s, and explained the terrible reality of what life was like for him.

He wrote: “I have come to understand that Monmouth School’s particular contribution… was a degree of brutality, expressed through a considerable number of its teachers… it has also left extremely deep psychological scars in my life, the result of intense trauma…there are many who have suffered in silence over decades of their subsequent lives. Not only from Monmouth, but certainly from there too. And yet the school, and society in general, continues to turn a blind eye to the results of brutalising young lives. It is a tragedy”.

My dad, Robert Parry, was a teacher at the school, too, so I didn’t have it as bad as others.

Now it appears the tragedy this man has spoken of is being exposed, as its awful legacy, in other schools is, finally, coming out.

The author Louis de Bernières boarded at Grenham House prep school between the ages of eight and 13. The school has since closed. After he spoke out about his experiences there, one reader said of his own school: “Punishment was varied, with most of it being corporal or having to run a certain distance in a certain time. One boy was expelled for punching his housemaster after his housemaster had beaten him. I have always admired the boy for doing that”.

Another ‘victim’ of the private/public school system, from Clyro in Powys wrote: “I lost my confidence and was terrified of public speaking for many years. At the age of 15 I started to rebel but this horrible school left me with very little in the way of education and very little desire to learn. Only years later did I do a degree — aged 66”. A further comment, which chimes with my own experience as a day boy, was: “The headmaster was a terrifying sadist. He waged a continuous war against the non-boarders, whom he referred to as ‘day-school horrors’. This was partly because many of them came to school by bus, which he reviled as being common. Any day-boy seen getting on or off a bus was beaten”.

A different remark also shed light on the terrible ordeal at this kind of school: “Between the ages of 10 and 12, I received 32 beatings for being naughty. You would wait for up to one week, where you and everybody knew that on the Friday evening, while you and all the boys were in bed, and just before lights out, the housemaster would come to the dormitory door and call your name. You would follow him into his study, where he would tell you that you had been naughty and tell you to bend over, then only wearing your pyjamas you would be beaten on your bottom with a gym shoe”.

I now have to undertake regular ‘therapy sessions’ over a cup of coffee with a friend across the road who went to Monmouth School in the 60s, and hates it more than I do, where we talk about what happened. He is the only one who understands!

“We can’t tell our wives about this, they simply wouldn’t understand”, he has said.

Maybe these sessions won’t be so relevant in future – if Labour get their way!

The memories of Phil’s remarkable decades-long award-winning career in journalism (after his years at Monmouth School) as he was gripped by the rare disabling neurological condition Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in a major book ‘A GOOD STORY’. Order the book now!

Regrettably publication of another book, however, was refused, because it was to have included names of living people.

Tomorrow – how worrying details in a damning report of the “sexist, misogynistic, racist and homophobic” culture inside Welsh rugby’s governing body, highlight revelations that one of the sport’s former star players was publicly condemned as “annoying as fuck” by a professional in the game, faced a barrage of criticism for his commentary style, and has been heavily criticised for a dangerous ‘prank’ with a fire extinguisher, which was posted on the internet.