- Spending energy - 12th March 2026

- Hidden in plain sight - 12th March 2026

- ‘M’lud I wish to delay proceedings…’ - 11th March 2026

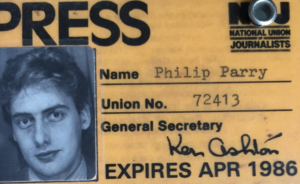

During 23 years with the BBC, and 40 years in journalism (when he was trained to use clear, simple language, avoiding jargon), working in a free environment has always been critical for our Editor, Welshman Phil Parry, but now there is more evidence of the reverse happening in Russia after an artist was jailed for replacing price tags in a supermarket with anti-war messages.

Earlier he described how he was assisted in breaking into the South Wales Echo office car when he was a cub reporter, recalled his early career as a journalist, the importance of experience in the job, and made clear that the‘calls’ to emergency services as well as court cases are central to any media operation.

He has also explored how poorly paid most journalism is when trainee reporters had to live in squalid flats, the vital role of expenses, and about one of his most important stories on the now-scrapped 53 year-old BBC Wales TV Current Affairs series, Week In Week Out (WIWO), which won an award even after it was axed, long after his career really took off.

He has also explored how poorly paid most journalism is when trainee reporters had to live in squalid flats, the vital role of expenses, and about one of his most important stories on the now-scrapped 53 year-old BBC Wales TV Current Affairs series, Week In Week Out (WIWO), which won an award even after it was axed, long after his career really took off.

Phil has explained too how crucial it is actually to speak to people, the virtue of speed as well as accuracy, why knowledge of ‘history’ is vital, how certain material was removed from TV Current Affairs programmes when secret cameras had to be used, and some of those he has interviewed.

He has disclosed as well why investigative journalism is needed now more than ever although others have different opinions, how the coronavirus (Covid-19) lockdowns played havoc with media schedules, and the importance of the hugely lower average age of some political leaders compared with when he started reporting.

We forget how lucky we are.

As journalists we work in a (relatively) free environment and are able to hold people to account, whereas in other countries the opposite is the case.

For example, in Russia an artist and activist is now at the start of a long prison sentence for replacing price tags in a St Petersburg supermarket with anti-war messages.

On November 16 Alexandra Skochilenko, was jailed for seven years for putting up messages such as: “My great-grandfather did not fight in ww2 so that Russia could become a fascist state and attack Ukraine”. From the other direction, one ultra-nationalist dissenter, Igor Girkin, a retired soldier and blogger, has been jailed for complaining that Vladimir Putin is not fighting forcefully enough.

All of this follows other disturbing events – which would have been funny were they not true.

Journalist Yulia Starostina was fined over half a million pounds (50,000 roubles) after she gave an interview to Dozhd, in which she described her anti-war tattoo. During the interview she explained it by talking about how she felt responsible for the war in Ukraine, and believed it was necessary to stop it.

She is not alone as an example of outrageous behaviour by the authorities either, and more absurd instances have come to light in Russia.

Alexei Moskalyov was sentenced to two years in a penal colony for discrediting the country’s army over his 13 year old daughter’s anti-war artwork. Social media posts by him have emerged which they didn’t like as well.

A Moscow baker who made anti-war cakes was fined for ‘discrediting’ the Russian army. Anastasia Chernysheva began sharing images of her cakes on social media soon after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Some of the cakes were decorated in the yellow and blue of the Ukrainian flag, while others had anti-war slogans or symbols. The baker was detained by officers, the human rights monitoring website OVD-Info has reported, citing her lawyer.

The number of these ridiculous instances is likely to grow, too, for journalists as well as ordinary citizens.

Valery Fadeyev the chairman of Russia’s ‘Human Rights’ Council, has proposed to define the concept of “Russophobia” at legislative level and called for a law to deter it. He declared: “Our task today is to try to formulate legally what Russophobia is and what articles of the criminal code can be used under this qualification, and if there is no such article, then an additional article must be introduced”.

At least 500 journalists have been forced to flee Russia since its invasion of Ukraine, according to Proekt Media, an investigative outlet, and are reporting the truth about the war from OUTSIDE the country! They call this “offshore journalism”, and the journalists are scattered across Europe, in cities such as Riga, Tbilisi, Vilnius, Berlin and Amsterdam, where they manage to reach a large audience, with most of them under the age of 40. “Our job today is to survive and not let our readers suffocate”, said Ivan Kolpakov, the editor-in-chief of Meduza, a news website.

Meduza has reported on the massacre of Ukrainian civilians in Bucha, and the extraordinary number of convicts that joined the mercenary group Wagner.

Mediazona, an online outlet founded by two members of ‘Pussy Riot’, a punk band which staged protest concerts, is trying to count the true number of Russian casualties. In 2012, three members of the band were all convicted of “hooliganism motivated by religious hatred” and each sentenced to two years’ imprisonment.

Mediazona has found an ingenious way to work out how many Russians have been conscripted, by analysing open-source data on the unusually high number of marriages since mobilisation began. (Draftees are allowed to register their marriage on the same day as they are enlisted, and often do, since they don’t know when, or if, they will see their partners again). Mediazona estimated that half a million people were drafted in the first round of conscription—far more than the 300,000 the Kremlin said would be.

tv Rain, Russia’s best known independent television channel, went dark eight days after the war started. Echo of Moscow, a radio station with five million listeners, became silent on the same day. Soon after that, Novaya Gazeta, the most outspoken critical newspaper in Russia, stopped printing.

Alexei Venediktov, the editor of Echo, and Dmitry Muratov, the Nobel prize-winning editor of Novaya Gazeta, stayed in Russia while some of their former colleagues set up operations offshore.

tv Rain is back on air, now based in Latvia and broadcasting via YouTube to 20 million viewers a month (although it has been ordered to shut its terrestrial output by the media regulator), most of them inside Russia. Echo is in Berlin,streaming news and talk-shows live via a new smartphone app, which the Kremlin tried but failed to block.

Roman Dobrokhotov, who runs The Insider said: “There is plenty of demand for investigative journalism, there are people who know how to do it and there is no shortage of subjects to investigate”.

Officials never approved of the sort of investigative reporting such as I undertake, and now it has built great walls around the truth, closing some 260 publications. With Twitter/X, Facebook and Instagram blocked, they are accessible today only via VPN proxies.

As I have shown, laws ban discrediting the Russian army (punishable by fines as was suffered by Ms Starostina, or jail as Mr Moskalyov endured), or publishing ‘fake news’ (punishable by prison) about the army.

Meanwhile, a new documentary film by independent journalist Jake Hanrahan has shed light on the “partisan” fight against the Kremlin. He has produced a YouTube film, which interviewed two members of an “anarcho-communist” group known as BOAK, whose aims were vague and unrealistic before the invasion of Ukraine.

Fires that have broken out across Russia have been blamed on Ukrainian saboteurs and even Western intelligence operatives, according to Radio Free Europe, but Mr Hanrahan suggests a “large-scale, active resistance inside Russia” is now active.

A list, updated on December 1, criminalises any discussion of over 60 sensitive subjects, from the numbers of Russians killed in action to the country’s mobilisation campaign, and anyone who wants an alternative view has to search hard for it. It is difficult to find a VPN that the security services haven’t already blocked.

So remember – we are lucky!

The memories of Phil’s extraordinary decades long award-winning career in journalism (when he could operate in a free environment) as he was gripped by the rare and incurable, neurological disabling condition Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in a major book ‘A Good Story’. Order it now.

The memories of Phil’s extraordinary decades long award-winning career in journalism (when he could operate in a free environment) as he was gripped by the rare and incurable, neurological disabling condition Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in a major book ‘A Good Story’. Order it now.

Regrettably publication of another book, however, was refused, because it was to have included names.