- Return to sender - 20th February 2026

- Legal eagle - 19th February 2026

- Round Robin - 19th February 2026

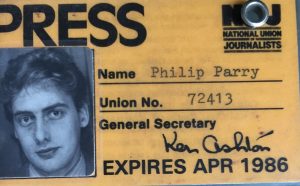

Here our Editor Phil Parry looks at the importance for keeping politicians on their toes of having a free and inquiring media, but which is under threat today as never before.

In the past he has described how he was helped to break into the South Wales Echo office car when he was a cub reporter, recalled his early career as a journalist, the importance of experience in the job, and making clear that the‘calls’ to emergency services as well as court cases are central to any media operation.

He has also explored how poorly paid most journalism is when trainee reporters had to live in squalid flats, the vital role of expenses, and about one of his most important stories presenting the now-scrapped 53 year-old BBC Cymru Wales (BBC CW) TV Current Affairs series, Week In Week Out (WIWO), which won an award even after it was axed, long after his career really took off.

Phil has explained too how crucial it is actually to speak to people, the virtue of speed as well as accuracy, why knowledge of ‘history’ is vital, how certain material was removed from TV Current Affairs programmes when secret cameras had to be used, and some of those he has interviewed.

Earlier he outlined why investigative journalism is needed now more than ever although others have different opinions, and how information from trusted sources is crucial at this time of crisis.

I know for a fact that government policy has been changed (slightly) as a result of my inquiries.

A lot of government ministers have become extremely angry when I have questioned them about their actions, and it was obvious they were very nervous about being asked about their policy.

I have endured appalling abuse, even threats both legal and illegal, from others when I have exposed wrong-doing.

To me these simple facts, underline the importance of having a free and inquiring media across the globe to keep ministers and others on their toes when they make decisions which affect everyone’s lives.

Sadly though, this kind of freedom is under threat as never before.

The ‘law’ has been used extensively, to silence ‘trouble-making’ journalists like me.

Last month seven Chinese state-security officers told Bill Birtles, an Australian journalist in Beijing, that he was ‘involved’ in a case and he was ordered not to leave China although eventually he did so.

At the same time in Shanghai six police officers visited the flat of another Australian journalist, Michael Smith, to deliver a similar message.

In recent years, another way of silencing journalists has proliferated; the use of what are known as Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation, or SLAPPs, where defamation or criminal lawsuits are brought with the intention of shutting down forms of expression such as peaceful protest or writing blogs.

Originally regarded as an American legal mechanism, such lawsuits are now fairly widespread in Europe.

Věra Jourová, the vice-president of the European Commission, the executive branch of the EU, has been working on introducing protections against SLAPP lawsuits, the defence of which can cost individuals a fortune and tie up their time and resources.

In France, media organisations and NGOs have been hit with what they view as SLAPP suits for publishing accusations of land-grabbing from villagers and farmers in Cameroon by companies associated with the Bolloré Group.

In the UK, fracking companies including Ineos, UK Oil & Gas, Cuadrilla, IGas and Angus Energy have since 2017 sought and been granted wide-ranging court injunctions, often directed against persons unknown, to prevent protests and campaigning activities at drilling sites.

Alongside SLAPP lawsuits, there are more traditional ways to keep journalists quiet.

More than 150 countries retain some sort of criminal defamation law, and many of them include the possibility of imprisonment as punishment.

Blasphemy and insult laws remain commonplace in many countries, and are often used by politicians, government officials, and civilian parties, against any critical media.

A number of countries including Turkey and Egypt have expansive definitions of ‘terrorism’ that allow them to arrest and detain anyone who voices political dissent or opposition, including journalists.

In countries such as Hungary and Poland, governments and their political allies exercise quasi-legal control of public information.

Media owners can be pressured on what content to publish by threats to limit access to finance and advertising revenues.

By the end of 2018, the Council of Europe’s Platform for the Protection of Journalism and Safety of Journalists, set up to record information on serious concerns about media freedom and the safety of journalists in Council of Europe (CoE) member states, had registered more than 500 alerts, with year-on-year rises of incidents in every year except 2017.

The majority of threats came from the state, with physical attacks and detentions making up nearly half the alerts.

Since 2015, only 11 per cent of all alerts have been marked as resolved.

Interviews with journalists echo these statistics.

In 2017, a study that interviewed 940 journalists from all CoE member states found that a staggering 40 per cent of them had suffered slander or worse.

I don’t think I was in that study.

But I could have been!

Tomorrow – more alarming revelations about a controversial Welsh rugby commentator who has been accused by fans of being ‘thick’ and appears to flout social media guidelines.

Phil’s memories of his astonishing 37-year award-winning career in journalism (when he has endured numerous threats) as he was gripped by the rare neurological disabling condition Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in a major book ‘A GOOD STORY’. Order the book now!