- Chinatown - 10th March 2026

- Dark speak easy part two - 9th March 2026

- Cyber bullying - 6th March 2026

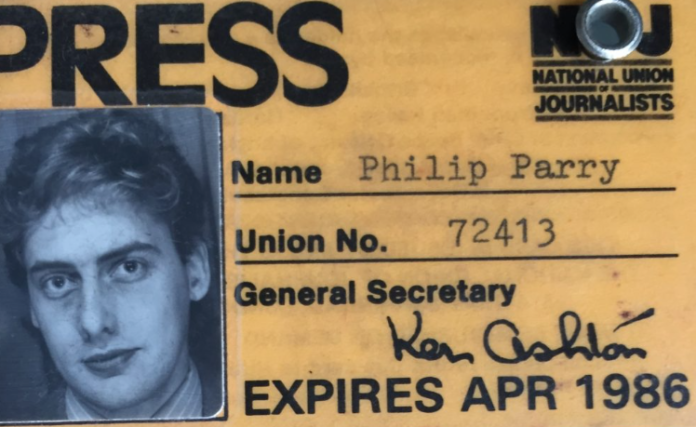

During 23 years with the BBC, and 39 years in journalism (when he was trained to use simple language, avoiding jargon), communication has always been central for our Editor, Welshman Phil Parry, and as the war in Ukraine enters its second year, here he looks at how it has speeded up change.

Previously he has described how he was helped to break into the South Wales Echo office car when he was a cub reporter, recalled his early career as a journalist, the importance of experience in the job, and made clear that the ‘calls’ to emergency services as well as court cases are central to any media operation.

He has also explored how poorly paid most journalism is when trainee reporters had to live in squalid flats, the vital role of expenses, and about one of his most important stories on the now-scrapped 53 year-old BBC Cymru Wales (BBC CW) TV Current Affairs series, Week In Week Out (WIWO), which won an award even after it was axed, long after his career really took off.

He has also explored how poorly paid most journalism is when trainee reporters had to live in squalid flats, the vital role of expenses, and about one of his most important stories on the now-scrapped 53 year-old BBC Cymru Wales (BBC CW) TV Current Affairs series, Week In Week Out (WIWO), which won an award even after it was axed, long after his career really took off.

Phil has explained too how crucial it is actually to speak to people, the virtue of speed as well as accuracy, why knowledge of ‘history’ is vital, how certain material was removed from TV Current Affairs programmes when secret cameras had to be used, and some of those he has interviewed.

Earlier he disclosed why investigative journalism is needed now more than ever although others have different opinions, and how information from trusted sources is crucial.

The most central thing for all reporters is getting your copy back to base, so that your audience can read or hear the story.

In the old days this was a long and laborious task – but now communication has broken out for everyone to use it, rather than broken down.

Formerly, if you were on newspapers when in the field, you would have to look for a house which had a telephone line, and then knock on the door to ask if you could use the phone in a transfer charge call, to dictate your story back to a copy-taker standing by in the newsroom.

If you were in broadcasting it was just as difficult.

In television the pictures were obviously fundamental, so you would either physically drive the tape back to the office, or find a special mast in the middle of nowhere to transmit them back, where a friendly (hopefully!) operator was able to take them in, and they could be cut before broadcast.

On BBC Wales Today (WT) in the late 1980s, I had to have a photograph taken holding a telephone, in case I was covering a story, but could only get to a phone box, so they could put that up instead of the pictures!

Radio reporters had it just as hard.

On May 29 1982 Robert Fox had just witnessed 36 hours of intense warfare at Goose Green, on the Falkland Islands, then being fought over by Britain and Argentina. It was the decisive battle of the war and it had gone Britain’s way.

Mr Fox, then a BBC Radio correspondent, was keen to tell listeners, but it took him 10 HOURS to get to a satellite phone aboard a warship, and another eight to decrypt his text in London, so the story was not actually broadcast for 24 hours!

Now everything is different, and a different war (this time in Ukraine) is a prime example of it. Indeed it has speeded up progress.

When the southern Ukrainian city of Kherson was liberated in November, it took just hours, if not minutes, for the news to flood out.

Images circulating on Telegram, a messaging service popular in Russia and Ukraine, showed Ukrainian soldiers strolling into the centre of the city, and Ukrainian flags flying over buildings.

A network of amateur analysts on Twitter tracked the Ukrainian advance, almost in real time, by ‘geo-locating’ the images – comparing trees, buildings as well as other features, to satellite imagery on Google Maps and similar services.

The rise of Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT), has also transformed the way that people receive news.

In the run-up to war, commercial satellite imagery and video footage of Russian convoys on TikTok, allowed journalists and researchers to corroborate Western claims that Russia was preparing an invasion. OSINT even predicted its onset.

During the Kherson offensive, Synthetic-Aperture Radar (SAR) satellites, which can see at night and through clouds, showed Russia building pontoon bridges over the Dnieper river before its retreat and, later, Russia’s army building new defensive positions along the M14 highway on the river’s left bank.

When Ukrainian drones struck two air bases deep inside Russia on December 5, high-resolution satellite images showed the extent of the damage, so reporters could assess the extent of it, and nail the fact that Russian officials had lied about the fact.

Unfortunately lies are still prevalent, but reporters and others can use new technology to verify the truth.

No more knocking on people’s doors to use their phone!

The memories of Phil’s decades long award-winning career in journalism (when getting the news out to the audience was all-important) as he was gripped by the rare neurological disease Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in a major book ‘A GOOD STORY’. Order it now!

Publication of another book, however, was refused, because it was to have included names.

Tomorrow – how MORE details about the atrocious alleged behaviour of serving police officers, have AGAIN focused attention on the actions of some at South Wales Police (SWP).