- Rocket man - 2nd March 2026

- Death wish two - 2nd March 2026

- News to celebrate! - 1st March 2026

Here our Editor Phil Parry looks at the huge privileges of being a journalist.

Earlier he has described how he was helped to break into the South Wales Echo office car when he was a cub reporter, recalled his early career as a journalist, the importance of experience in the job, and making clear that the ‘calls’ to emergency services as well as court cases are central to any media operation.

He has also explored how poorly paid most journalism is when trainee reporters had to live in squalid flats, the vital role of expenses, and about one of his most important stories on the now-scrapped 53 year-old BBC Cymru Wales TV Current Affairs series he presented for 10 years, Week In Week Out (WIWO), which won an award even after it was axed, long after his career really took off.

Phil has explained too how crucial it is actually to speak to people, the virtue of speed as well as accuracy, why knowledge of ‘history’ is vital, how certain material was removed from TV Current Affairs programmes when secret cameras had to be used, and some of those he has interviewed.

He has also disclosed why investigative journalism is needed now more than ever although others have different opinions, and how information from trusted sources is crucial at this time of crisis.

Journalists are lucky.

We dip into people’s lives, hear incredible stories and experience astonishing things.

For example long before I started The Eye, I was privileged to interview several veterans of the First World War, who told me of extraordinary events they were involved in, memories of which they have been forced to carry through the rest of their lives.

They were, of course, all old men then and have now long since died.

One old man told me of how he went over the top and his best friend was killed beside him.

As the young man lay dying on the ground with his guts in his hands, he said to him: ‘If my mother could see me now’.

The elderly gentleman I was interviewing then said to me: “He was only 18”.

I looked at him and his eyes were full of tears.

For that same WIWO Current Affairs programme, I was filming in northern France, and the expert I was interviewing bent down during our discussion to pick up a British bullet which was caked in mud, and must have been fired more than 70 years before!

For that same WIWO Current Affairs programme, I was filming in northern France, and the expert I was interviewing bent down during our discussion to pick up a British bullet which was caked in mud, and must have been fired more than 70 years before!

All kind of armaments were easily discovered.

You would drive round a corner and see a pile of (live) shells which had been neatly stacked by the farmer who had found them as he ploughed his field.

I have regularly been to the homes of poorer people.

They would invariably be extremely tidy – although this wasn’t always the case – but there was usually exactly the same smell; a mixture of cheap cigarettes, dirty carpets and damp.

Drugs were often a major factor.

I remember filming one woman in her council house in Manchester for Panorama and she kept interrupting the interview to go to the back door.

Only afterwards did I realise she was dealing in drugs.

I have lost count of the number of rough estates I have been on to secure a key interview.

On one near Cardiff there were spikes around strategically-placed CCTV cameras.

It struck me then that if people were dehumanised in this way, it is hardly surprising that they might behave in a less than acceptable manner.

But the roughest estate was probably in Nottingham where I was filming, this time for the BBC Two programme Public Eye.

We were conducting an interview in the kitchen of one person’s house, but there was no door – just a piece of cardboard with a hole in it.

The best places to film in were, bizarrely, jails because it was a controlled environment (by which I mean that as well as the inmates being cowed because they saw that we had security, we were also not subject to being constrained by bad weather), and the prisoners were so bored they were more than happy to talk to us about their lives.

In one sex offenders prison in Wales I gave the subjects a ‘hard’ time during the interviews about what they had done, then left them mentally collapsed and hating themselves.

There was a complaint afterwards from the authorities that they had to pick up the pieces, and I should have left them in a more upbeat mood, but that was difficult after what they had done.

In another prison in Wales a young man told me cheerfully how he had broken into an old woman’s house to burgle it, and I thought at the time how devastating that must have been for the homeowner.

I remember he said he would always confess to what he HAD done, but never to what he HADN’T when the police tried to fit him up for something he didn’t do, which, I am afraid to say, happened all too often.

But this, like all the other ones, was an extraordinary event.

But this, like all the other ones, was an extraordinary event.

It was, in fact, a privilege to talk to him – as with all the other people.

Tomorrow – shocking revelations about the background to a company which claimed it was coming to Wales and would create thousands of jobs, but has now announced it will not.

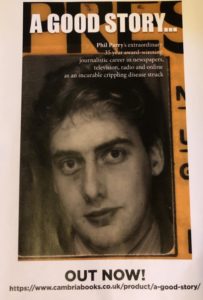

Phil’s memories of his remarkable decades-long award-winning career in journalism (including some of the people he has interviewed) as he was gripped by the rare disabling neurological condition Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in a major book ‘A GOOD STORY’. Order the book now! The picture doubles as a cut-and-paste poster!