- Dark speak easy part two - 9th March 2026

- Cyber bullying - 6th March 2026

- Fight club - 5th March 2026

During 23 years with the BBC, and 40 years in journalism, our Editor, Welshman Phil Parry, was often confronted by official secrecy (as well as its damaging effects), so regularly had to use subterfuge to get at the truth, and this is now highlighted by reports that Ukraine’s grindingly slow counter-offensive (despite recent successes) may have been harmed by strategists keeping plans close to their chests.

Earlier Phil has described how he was helped to break into the South Wales Echo office car when he was a cub reporter, recalled his early career as a journalist, the importance of experience in the job, and making clear that the ‘calls’ to emergency services as well as court cases are central to any media operation.

He has also explored how poorly paid most journalism is when trainee reporters had to live in squalid flats, the vital role of expenses, and about one of his most important stories on the now-scrapped 53 year-old BBC Wales TV Current Affairs series, Week In Week Out (WIWO), which won an award even after it was axed, long after his career really took off.

He has also explored how poorly paid most journalism is when trainee reporters had to live in squalid flats, the vital role of expenses, and about one of his most important stories on the now-scrapped 53 year-old BBC Wales TV Current Affairs series, Week In Week Out (WIWO), which won an award even after it was axed, long after his career really took off.

Phil has explained too how crucial it is actually to speak to people, the virtue of speed as well as accuracy, why knowledge of history and teaching the subject is vital, how certain material was removed from TV Current Affairs programmes when secret cameras had to be used, and some of those he has interviewed.

He has disclosed as well why investigative journalism is needed now more than ever although others have different opinions, how the coronavirus (Covid-19) lockdown played havoc with media schedules, and the importance of the hugely lower average age of some political leaders compared with when he started reporting.

The default setting should be transparency.

Obviously there are certain areas where secrecy is needed – such as not to give information to an enemy, or to protect the lives of key government personnel.

But, frankly, these are few and far between, and keeping things secret simply for the sake of it, is extremely corrosive.

It leads to a ‘bunker-mentality’ in organisations, of ‘we are right, and outsiders shouldn’t question us’, so insiders (potential whistleblowers) are afraid to speak out about processes which are wrong, fearing for their jobs.

This has meant, unfortunately, that I have often had to use subterfuge to establish the facts.

Apart from knocking on doors during investigations, I have also used secret recordings, posed as a long-lost relative, and kept a whirring tape recorder in my bag.

For one BBC TV Panorama programme I presented, I wore a hidden camera in my tie which became very hot.

I kept having to move my tie otherwise the heat would have become unbearable on my chest!

All of this was because practices were kept secret.

The spotlight has been thrown onto this kind of secretive behaviour because reports suggest it may have played a part in the slowness of Ukraine’s counter offensive against Russia, which has been going on since June.

There have been successes recently, but it has remained slow.

Ukraine has taken control of Andriivka and Klishchiivka – two villages on the southern flank of Bakhmut.

Three Russian brigades “likely suffered heavy losses”, according to the Institute for the Study of War (ISW).

However no major settlements have been liberated, the much-vaunted ‘land bridge’ to the sea hasn’t materialised, and in the beginning almost nothing seemed to happen as Ukrainian forces became bogged down in Russian defences.

American and UK officials worked closely with Ukraine in the months before the counter offensive was launched, and they gave the invaded country intelligence as well as advice.

Yet Ukraine then kept its own counsel – delaying the start of the offensive and holding plans close to its chest

Not even its own allies were in the loop.

The result has probably been that Russia has gained time to build up its formidable defences in the south – the so-called Surovikin line, named after a now-fired Russian general.

This has emphasised the damage which can be caused by an undue reliance on secrecy, and Ukraine is, sadly, not alone in this.

For example the UK’s Official Secrets Act 1989 is a huge improvement on what went before, but it still creates offences connected with the unlawful disclosure of official information in SIX categories by government employees.

What are journalists meant to do in finding out what is going wrong?!

One website, which offers advice to whistleblowers, tells them: “It’s important to remember…that you may not be protected if you break (the) law in blowing the whistle. For example, if you’ve signed the Official Secrets Act as part of your employment contract”.

In America there is a long history of whistleblowers exposing terrible practices, because of a culture of secrecy.

The extraordinary case of the trans soldier and whistleblower, Chelsea Manning, is only a more recent one.

Ms Manning (whose parents met while his father was serving at RAF Brawdy six miles from St David’s in Pembrokeshire) was convicted by court-martial in July 2013 of violations of the Espionage Act after disclosing to WikiLeaks nearly 750,000 classified, or unclassified but sensitive, military and diplomatic documents.

She was sentenced to 35 years at the maximum-security US Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth.

On January 17, 2017, Barack Obama commuted her sentence to nearly seven years of confinement dating from Ms Manning’s arrest in 2010.

In 1969 – Ron Ridenhour revealed the Mai Lai massacre during the Vietnam War.

It had been kept secret that on March 16, 1968, a company of the 23rd Infantry Division killed up to 400 Vietnamese civilians, and he went on to become an investigative journalist like me.

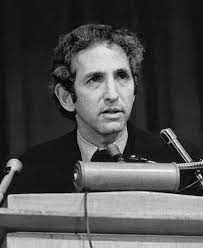

Two years later, in the same war, Daniel Ellsberg gave what came to be known as the ‘The Pentagon Papers’ to several newspapers. He showed how even though the public was led to believe by officials that the war was unwinnable, it was actually escalated.

But it hasn’t simply been government policy which has been exposed.

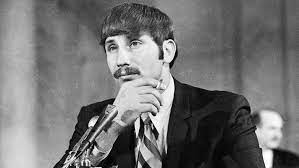

In 1971 – Frank Serpico blew the whistle on police corruption in New York in the late 1960s and 1970s.

Mr Serpico showed how bribes estimated to be in the millions of dollars were taken by police officers and their associates.

He, and a sympathetic officer, were forced to go to The New York Times to spill the beans.

Events like these only serve to show how harmful secrecy can be, and journalists HAVE to get involved.

Ukraine may know this to its cost…

The memories of Phil’s decades long award-winning career in journalism (during which he was often confronted with the awful effects of secrecy and was forced to turn to undercover methods) as he was gripped by the incurable neurological condition, Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in a major book ‘A GOOD STORY’. Order it now!

Publication of another book, however, was refused, because it was to have included names.

Tomorrow – Phil looks at how the Russell Brand saga, highlights the fact that there have been an extraordinary number of scandals to have erupted, with the BBC at their heart.