- Fight club - 5th March 2026

- Polls apart - 4th March 2026

- Repeating on you… - 4th March 2026

Here our Editor Phil Parry looks at how the lockdown rules showing Wales effectively falling into line with England (or the other way around) highlight the inconsistencies of devolution.

Earlier he has described how he was helped to break into the South Wales Echo office car when he was a cub reporter, recalled his early career as a journalist, the importance of experience in the job, and making clear that the ‘calls’ to emergency services as well as court cases are central to any media operation.

He has also explored how poorly paid most journalism is when trainee reporters had to live in squalid flats, the vital role of expenses, and about one of his most important stories on the now-scrapped 53 year-old BBC Cymru Wales TV Current Affairs series he presented for 10 years, Week In Week Out (WIWO), which won an award even after it was axed, long after his career really took off.

Phil has explained too how crucial it is actually to speak to people, the virtue of speed as well as accuracy, why knowledge of ‘history’ is vital, how certain material was removed from TV Current Affairs programmes when secret cameras had to be used, and some of those he has interviewed.

He has also disclosed why investigative journalism is needed now more than ever although others have different opinions, and how information from trusted sources is crucial at this time of crisis.

Devolution of UK power from Westminster has been one of the most important post-Second World War developments – yet it has also been one of the most controversial, and the extraordinary events now have thrown this issue into sharp relief.

Perhaps I know this more than most as I have travelled all over Wales for years, presenting programmes.

Whereas in the early stages of the lockdown, having devolved administrations was seen to have worked well, it is now viewed as an impediment.

Devolution was always as much of a political and cultural move, as it has been economic, and one that was embedded in reality, and the present crisis has put that fact centre stage.

The so-called ‘architect’ of devolution, former Welsh Secretary Ron Davies, told me once of how devolution was a process not an event.

In this he was echoing a pamphlet published ahead of the first elections to the new National Assembly for Wales (as it was then called) in May 1999, in which he explained: “Devolution is a process. It is not an event and neither is it a journey with a fixed end-point. The devolution process is enabling us to make our own decisions and set our own priorities, that is the important point. We test our constitution with experience and we do that in a pragmatic and not an ideologically driven way”.

But this description of devolution has been put under severe strain by the coronavirus/Covid-19 lockdown.

At the beginning, the First Minister of Wales (FMW) Mark Drakeford was seen to have covered himself in glory by appearing to be tougher in his response than the much-derided UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

But now Mr Johnson’s measures are seen as equally tough (if belated), and Mr Drakeford’s own pre-Christmas announcement (which was similar) came minutes after the UK Prime Minister’s.

Wales was placed under lockdown from midnight on December 19 with festive plans scrapped for all but Christmas Day, and the severe restrictions are likely to continue for many more months.

But this was nearly indistinguishable from the announcement by Mr Johnson moments earlier.

He said that the planned relaxation of lockdown rules for Christmas had been ditched for large parts of south-east England, and it was cut to just Christmas Day, for the rest of England, which, according to several newspapers, was ‘the nation’.

Yet I have always had a problem with that word ‘nation’, even though it has been used with gay abandon over the lockdown.

There are in fact a number of ‘nations’ which make up the United Kingdom: Wales, Scotland, England and (as a country, province or region, depending on where you come from) Northern Ireland.

But when people talk of ‘the nation’ they invariably mean the English one – there is, technically, no such thing as a British ‘nation’.

On the other hand the issue, say, of a Welsh ‘nation’ is a difficult concept.

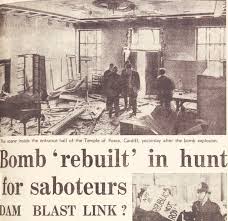

The spotlight was shone once again on this fundamental reality for me, by the death recently of the extremist John Jenkins, and the way it has been reported.

Jenkins was convicted of bombing-related offences intended to disrupt the investiture of the Prince of Wales, and he led the extreme Welsh nationalist group, Mudiad Amddiffyn Cymru (Movement for the Defence of Wales) (MAC) from 1964 until his arrest in 1969.

But the way his death was reported last month sparked huge outrage, with the morning newspaper which covers North Wales coming in for particular condemnation.

One reader complained on Twitter: “Tributes to man who Orchestrated a bombing campaign…..Disgraceful D.P…”.

Another said: “Shameful reporting. This man set out to kill with no conscience”.

Jenkins had conducted his bombing campaign to achieve an independent Welsh ‘nation’, but when the term ‘nation’ is mentioned, it usually means somewhere centred around the Lleyn Peninsula or possibly a place in Ceredigion.

The truth is that Wales is made up of a myriad of regions and places.

The borderlands (where I am from) have nothing in common with the South Wales valleys, apart from some similarities of accent.

West Wales is different again, and North West Wales (seen as a Welsh-speaking heartland) is a world away from North East Wales (where many people work in Liverpool or Manchester).

There is no single Welsh accent either – there are lots of them

When people talk of a Welsh accent, they usually mean someone from the South Wales valleys, but the accents of those from Monmouthshire are a mix of the South Wales valleys, the South West of England and the Forest of Dean, the West Wales accent has more of a lilt to it, while the North Wales and South Wales accents are as different as chalk and cheese.

Even within these regions there are huge differences – an accent can vary from valley to valley for instance.

This was hammered into my brain when I drove all over Wales as a Television and Radio reporter for years – first with the HTV (as it then was) Wales at Six (WaS) programme, then on BBC Cymru Wales Today (WT), next as the Current Affairs presenter for BBC Cymru Week In, Week Out (WIWO), and finally with BBC Cymru Radio Wales (RW).

Indeed I would suggest that there are few journalists who have moved the length and breadth of Wales as much as I have!

But perhaps politicians and others, don’t want to confront this awkward fact, yet it has been underlined with today’s remarkable situation…

Tomorrow – details of the main Welsh independence organisation where supporters are cancelling their membership.

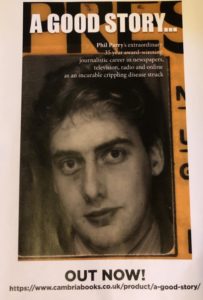

Phil’s astonishing decades-long award-winning career in journalism (which included covering the start of devolution in Wales) as he was gripped by the rare neurological disabling condition Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in the major book ‘A GOOD STORY’. Order the book now!