- Rocket man - 2nd March 2026

- Death wish two - 2nd March 2026

- News to celebrate! - 1st March 2026

After 23 years with BBC Cymru Wales (BBC CW), and 38 years in journalism (when he was trained to use clear and simple language, avoiding jargon), here our Editor Phil Parry looks at how today the question of nationhood has become a key battleground, but history shows that it is INCREDIBLY complex.

In the past he has described how he was assisted in breaking into the South Wales Echo office car when he was a cub reporter, recalled his early career as a journalist, the importance of experience in the job, and made clear that the ‘calls’ to emergency services as well as court cases are central to any media operation.

He has also explored how poorly paid most journalism is when trainee reporters had to live in squalid flats, the vital role of expenses, and about one of his most important stories on the now-scrapped 53 year-old BBC CW TV Current Affairs series, Week In Week Out (WIWO), which won an award even after it was axed, long after his career really took off.

Phil has explained too how crucial it is actually to speak to people, the virtue of speed as well as accuracy, why knowledge of ‘history’ is vital, how certain material was removed from TV Current Affairs programmes when secret cameras had to be used, and some of those he has interviewed.

He has disclosed as well why investigative journalism is needed now more than ever although others have different opinions, how the pandemic played havoc with media schedules, and the importance of the hugely lower average age of some political leaders compared with when he started reporting.

It is obvious that today the idea of a ‘national’ identity is being invoked ever more strongly, and it seems politicians and historians in Wales are part of this process.

The First Minister of Wales (FMW) Mark Drakeford, often cites the importance of Wales going its own way with restrictions during the Covid-19 pandemic, although this appears to be flexible.

For example, full crowds will be allowed to attend outdoor events from tomorrow, so professional sports teams can welcome back capacity stadiums from then.

It means Welsh rugby fans will be able to attend Wales’ first home Six Nations game at the Principality Stadium in Cardiff against Scotland on February 12.

This action by the FMW might appear to be convenient, given that there would have been an enormous outcry if Six Nations games had been played in an empty stadium in Wales, but full ones everywhere else!

The UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, was no less averse to playing the national card during the EU referendum. He said Britain (which probably meant England in reality, as it is by far the biggest home ‘nation’) would be “taking back control”, and has declared: “It would be a sad day if we British stopped being cynical, but you sometimes wonder whether we overdo it”.

His predecessor Theresa May, would talk about “this precious Union” when it suited her politically.

Historians too, should take their share of the blame for what has become a very blurred picture, although the argument is often deployed that the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland can be extremely powerful.

‘Englishness’, a book by Ailsa Henderson and (Welshman) Richard Wyn Jones, is, for instance, a scholarly testament to the union’s strengths. They have conducted since 2011, NINE big quantitative surveys of ‘Englishness’ which demonstrate that the number of people who describe themselves as exclusively or mainly ‘English’ rather than ‘British’ is growing, and that the idea of ‘Britishness’ – once the glue that held the UK together – is growing weaker.

Londoners use ‘British’ to signal their cosmopolitanism; the Scots and Welsh to signal their unionism.

The 2014 Scottish referendum stoked English grievances without satisfying the Scots, and the 2015 General Election turned a growing political division between the two (along with Wales) into a chasm, which was only made deeper when Mr Johnson was elected in 2019.

While England and Wales voted to leave the EU in 2016, the Scots voted against.

Many in England apparently feel that by pocketing more money than they create, the Scots and Welsh are not playing fair (Scottish Government funding per person is 31 per cent above English levels, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, and the cash Wales receives is proportionately much greater too). They believe that membership of the EU was wrong, because Parliament is the only legitimate source of power.

The building of the UK was, over a millennium, the story of England’s relentless (at times extremely brutal), expansion. First riding roughshod over the Celtic lands on its borders, then peoples across the world. The 1707 Act of Union brought Scotland and England ‘together’ yet was strongly resisted north of the border. A ‘union of crowns’, when James VI of Scotland also became James I of England, in 1603, was a kind of precursor.

Expositions of English (or if you prefer ‘British’) history have provided ‘our island nation’ with both a web of ties with the Anglosphere, and a unique global economic as well as strategic niche.

An understanding of history, and its teaching, is up there for an investigative journalist. It’s as important as a knowledge of the libel laws and past experience.

History has always played a prominent role for me. In order to construct a story it is important not simply to know that an event occurred, but the history of WHY it occurred.

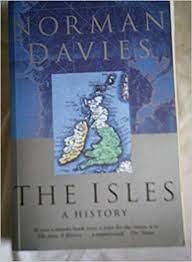

However, the historical idea of Britain as an ‘island’ is problematic. The historian Norman Davies called his book exploring nationhood ‘The Isles’ for that very reason.

One of the difficulties with English nationalism, in its newly radicalised and politicised form, is that it may be too big to be tamed, England accounts for 84 per cent of the British population (and growing) while Greater London has more people than Scotland and Wales combined.

One of the difficulties with English nationalism, in its newly radicalised and politicised form, is that it may be too big to be tamed, England accounts for 84 per cent of the British population (and growing) while Greater London has more people than Scotland and Wales combined.

It is not just in Britain either, that ‘national’ identity has become strong.

In the long-running dispute between Russia and Ukraine, this is regularly mentioned (and it is possible that the former is about to invade the latter because of it). In July, President Putin published a long article setting out his position on the two countries, in which he made clear that Ukraine was part of Russia, called “On The Historical Unity Of The Russians And The Ukrainians”.

Mr Putin wrote: “Ukrainians are very well aware that… their country does not really exist”.

In his 2015 book ‘The Gates of Europe’ the Ukrainian historian Serhii Plokhy declared: “Nation-building as conceived in a future New Russia makes no provision for a separate Ukrainian ethnicity in a broader Russian nation”.

We too should be aware that what Mr Putin says is not true, and it is only an extremely partial reading of history.

Wales may have a stronger claim to being a ‘nation’, but that is, as well, only one view from history…

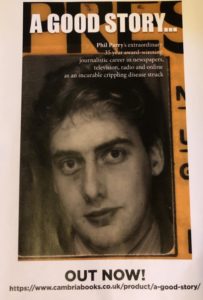

Welshman (although on the border with England!) Phil’s memories of his remarkable decades long award-winning career in journalism as he was gripped by the rare disabling condition Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in a major book ‘A GOOD STORY’. Order the book now!

Regrettably publication of another book, however, was refused, because it was to have included names.