- Cyber bullying - 6th March 2026

- Fight club - 5th March 2026

- Polls apart - 4th March 2026

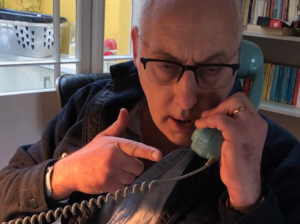

During a 40 year career (when he was trained to use simple language, avoiding jargon), our Editor, Welshman Phil Parry, has been lucky enough to work in a relatively free environment for journalists, and this is now underlined by the election victory of a moderate centre right party in Poland, which is likely to row back on politicisation of the media, although journalistic freedom is still under threat in other countries around the world.

Earlier Phil has described how he was helped to break into the South Wales Echo office car when he was a cub reporter, recalled his early career as a journalist, the importance of experience in the job, and making clear that the‘calls’ to emergency services as well as court cases are central to any media operation.

He has also explored how poorly paid most journalism is when trainee reporters had to live in squalid flats, the vital role of expenses, and about one of his most important stories on the now-scrapped 53 year-old BBC Wales TV Current Affairs series, Week In Week Out (WIWO), which won an award even after it was axed, long after his career really took off.

He has also explored how poorly paid most journalism is when trainee reporters had to live in squalid flats, the vital role of expenses, and about one of his most important stories on the now-scrapped 53 year-old BBC Wales TV Current Affairs series, Week In Week Out (WIWO), which won an award even after it was axed, long after his career really took off.

Phil has explained too how crucial it is actually to speak to people, the virtue of speed as well as accuracy, why knowledge of history and teaching the subject is vital, how certain material was removed from TV Current Affairs programmes when secret cameras had to be used, and some of those he has interviewed.

He has disclosed as well why investigative journalism is needed now more than ever although others have different opinions, how the coronavirus (Covid-19) lockdown played havoc with media schedules, and the importance of the hugely lower average age of some political leaders compared with when he started reporting.

It has been little commented upon, but the change for all journalists and their audiences, could be profound.

Donald Tusk’s centre-right Civic Coalition have effectively turfed out the ruling right-wing populist Law and Justice (PiS) group in Poland.

They have still to form a coalition, but it is likely that they will now, thankfully, restore independence to its public broadcaster, after it became a bull horn for the party.

Almost all the attention in the mainstream media was on how Mr Tusk could now unlock EU funds, by withdrawing the politicisation of the judiciary, but this might be just as significant. It will mean that families in Poland will have access to free and independent news, which the Government may not approve of.

The PiS had followed the example of Hungary’s populist Victor Orban (although disagreeing with him on key issues, like Ukraine) when it won power in 2015, and quickly turned TVP, the public television network, into a propagandist tool of the party.

Under the aegis of the PiS, the network championed campaigns against gay rights and demonised the opposition mayor of Gdansk, who was assassinated by an extremist in 2019.

Yet the BBC didn’t mention this at all in its initial report on the victory of Mr Tusk, concentrating instead on the percentage of votes cast, and the likelihood of a coalition. In a large piece, The Times said merely: “Tusk is also likely to restore balance to the country’s public broadcasters, which are led by PiS loyalists and have heavily favoured the government in their coverage”.

However this could be hugely important (if it happens), and might pave the way for an independent media in other countries where it has been appallingly undermined.

However this could be hugely important (if it happens), and might pave the way for an independent media in other countries where it has been appallingly undermined.

Evidence shows that media freedom is being restricted in most countries. According to the World Press Freedom Index (WPFI) 2023 – which evaluates the environment for journalism in 180 countries or territories, and is published on World Press Freedom Day (WPFD) (May 3) – the situation is “very serious” in 31 countries, “difficult” in 42, “problematic” in 55, and “good” or “satisfactory” in only 52 countries. In other words, the environment for journalism is ‘bad’ in seven out of 10 countries. Norway was ranked first for the seventh year running, with Ireland second, and Denmark third. The last three places were occupied solely by Asian states, with North Korea at the bottom of 180 countries.

In the EU there is official recognition of media freedom with it saying last year: “The European Commission adopted today a European Media Freedom Act, a novel set of rules to protect media pluralism and independence in the EU. The proposed Regulation includes, among others, safeguards against political interference in editorial decisions and against surveillance…”.

In the EU there is official recognition of media freedom with it saying last year: “The European Commission adopted today a European Media Freedom Act, a novel set of rules to protect media pluralism and independence in the EU. The proposed Regulation includes, among others, safeguards against political interference in editorial decisions and against surveillance…”.

But these fine words belie the reality.

For example, after Slovenia seceded from Yugoslavia in 1991, it gave Radio Television of Slovenia (RTV-SLO) a mandate to report independently, unlike the state ‘information’ that passed for news under communism. Yet the Government there is now refusing to pay RTV-SLO’s budget, and wanted to pass a new media law that will make it easier to control.

In the Netherlands the situation appears almost as bad. Reporters on the national public news broadcaster, the NOS, have been physically attacked at protests, and while reporting on Covid-19 measures. The NOS removed its logo from its satellite vans after they were repeatedly harassed in traffic.

In Latvia, the chief risk is the legal and financing structure. The country’s new public-media law failed to include a set-aside tax, like the television licence fee that funds the BBC (which could now be cut after the Martin Bashir affair), and that leaves it vulnerable to political pressure, while it is not clear that the supervisory board will be protected from political appointments.

When Mr Orban won power in Hungary in 2010 he adapted Vladmir Putin’s blueprint, transforming the state media agency MTVA into a propaganda organ. The group was restructured into a shell company in a fashion that exempted it from the law governing public media, and during the European Parliament (EP) elections in 2019, editors at MTVA were recorded instructing reporters to favour Mr Orban’s Fidesz party.

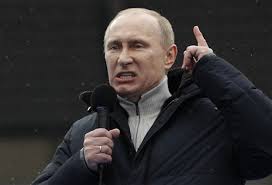

However outside the EU, the problems facing an independent media are even worse. The prime example, of course, is Russia where RT (Russia Today) is accused of being a mouthpiece for Mr Putin. By the mid-2000s Russian news shows’ agendas were being set at government-led meetings.

Mr Putin signed a law that lets Russia declare journalists and bloggers “foreign agents” in a move that critics say will allow the Kremlin to target government critics.

Under the vaguely worded law, Russians and foreigners who work with the media or distribute their content and receive money from abroad would become ‘enemies of the state’, potentially exposing journalists, their sources, or even those who share material on social networks to foreign agent status.

In Belarus the situation is also appalling. At least 16 journalists there are behind bars, and riot police are singling out reporters for arrests and beatings at protests as the media is intimidated.

The embattled dictator Alexander Lukashenko, forced a Ryanair passenger plane to make an unscheduled stop in his capital in order to arrest the editor of an internet channel, NEXTA, that has been reporting on his crackdown. Roman Protasevich was taken off the plane, which was flying from Athens to Vilnius, the Lithuanian capital. Citing what it said was ‘evidence’ that there were explosives on board, the authorities forced the aircraft to land in Minsk as it passed through Belarusian airspace on its way to neighbouring Lithuania, sending a MiG fighter plane to escort the Ryanair jet down. The state news agency later reported that no explosives had been found, and it seems certain that the incident was invented purely as a way of arresting the journalist.

The alarming details came after Marina Zolotova, the editor of Tut.by, an independent news website in the counrry, said: “Blue press jackets and press badges have become targets. When journalists go to cover a protest they cannot be sure that they will come home. This is a real war by the authorities against independent journalism and their own people.”

It is clear that Mr Lukashenko is waging a war against journalists who have dared to report on his regime’s brutal crackdown against peaceful protesters. At least eight protesters were killed and hundreds more have alleged torture and rape, in police custody. Among the most high-profile of those in prison is Yekaterina Bakhvalova, who was arrested as she filmed riot police firing stun grenades into a crowd demonstrating against the death in police custody of a fellow protesters.

Around the world it seems to be becoming worse for media freedom and investigative journalism, (although Poland might soon be an exception). Dozens of reporters covering the anti-racism protests after the killing of the unarmed black man George Floyd that rocked the US, were apparently targeted by security forces using tear gas, rubber bullets and pepper spray. In many cases, the reporters said they were attacked despite showing clear press credentials.

Such assaults “are an unacceptable attempt to intimidate (reporters)“, said the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), a New York-based lobbying group. Attacks on journalists carried out by protesters have also been reported. The arrest of a CNN news crew live on air in Minneapolis, first drew global attention to how law enforcement authorities in the city were treating reporters covering the protests. In total, the Press Freedom Tracker (PFT), a non-profit project, says it is examining more than 100 “press freedom violations” at protests. About 90 cases involve attacks.

In the past I have been called online (wrongly), a “bastard”, a “liar”, a “misogynist”, a “little git”, and (accurately), a “troublemaker”, a “nuisance”, “irritating”, as well as “annoying” but this pales into insignificance with what is happening elsewhere around the globe.

At least suppression of an independent media might not happen in Poland in future, so we can be hopeful – for now at least!

Details of Phil’s astonishing decades-long journalistic career (when insults because of his stories were mercifully rare at the beginning), as he was gripped by the incurable neurological condition Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in an important book ‘A GOOD STORY’. Order it now.

Regrettably publication of another book, however, was refused, because it was to have included names.

Tomorrow, how Phil has watched as the long slow decline of manufacturing (not least in Wales) has been decried, but new figures show that the sector is doing fairly well.