- Cyber bullying - 6th March 2026

- Fight club - 5th March 2026

- Polls apart - 4th March 2026

During 23 years with the BBC, and 39 years in journalism (when he was trained to use clear, simple language, avoiding jargon), working in a free environment has always been critical for our Editor, Welshman Phil Parry, but now there is more evidence of the reverse, after a journalist in Russia was punished following a television interview in which she explained her tattoo.

So here he looks at this controversial situation, as well as how the war in Ukraine, seems to have spurred an independent Russian media, although it is based outside the country.

Earlier he described how he was assisted in breaking into the South Wales Echo office car when he was a cub reporter, recalled his early career as a journalist, the importance of experience in the job, and made clear that the‘calls’ to emergency services as well as court cases are central to any media operation.

He has also explored how poorly paid most journalism is when trainee reporters had to live in squalid flats, the vital role of expenses, and about one of his most important stories on the now-scrapped 53 year-old BBC Wales TV Current Affairs series, Week In Week Out (WIWO), which won an award even after it was axed, long after his career really took off.

He has also explored how poorly paid most journalism is when trainee reporters had to live in squalid flats, the vital role of expenses, and about one of his most important stories on the now-scrapped 53 year-old BBC Wales TV Current Affairs series, Week In Week Out (WIWO), which won an award even after it was axed, long after his career really took off.

Phil has explained too how crucial it is actually to speak to people, the virtue of speed as well as accuracy, why knowledge of ‘history’ is vital, how certain material was removed from TV Current Affairs programmes when secret cameras had to be used, and some of those he has interviewed.

He has disclosed as well why investigative journalism is needed now more than ever although others have different opinions, how the coronavirus (Covid-19) lockdowns played havoc with media schedules, and the importance of the hugely lower average age of some political leaders compared with when he started reporting.

It has always seemed important to me for journalists to work in a free environment, but now there is, sadly, even more evidence of the opposite being the case.

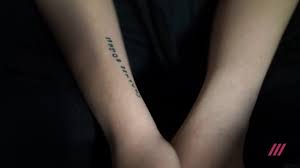

Journalist Yulia Starostina has been fined over half a million pounds (50,000 roubles) after she gave an interview with one of the few independent broadcasters left in Russia, Dozhd, in which she described her anti-war tattoo. During the interview she explained it by talking about how she felt responsible for the war in Ukraine, and believed it was necessary to stop it.

She is not alone as an example of outrageous behaviour by the authorities either, and more absurd instances have come to light in Russia.

Alexei Moskalyov was sentenced to two years in a penal colony for discrediting the country’s army over his 13 year old daughter’s anti-war artwork Social media posts by him have emerged which they didn’t like as well.

Even the financier of Russian mercenary group Wagner Yevgeny Prigozhin has weighed in over this ridiculous sentencing and called into question its legality.

Perhaps Mr Prigozhim should bear in mind the fact that Vladimir Putin has signed a law to prohibit “discrediting” and spreading “fake news” about ‘volunteers’ and mercenary groups like his fighting in Ukraine. The amended law sees anyone who criticises ‘volunteer’ forces and private mercenary units – including Wagner – from now on facing up to five years in prison, or a fine of 300,000 roubles (£3,200).

Meanwhile, as with Ms Starostina, a Moscow baker who made anti-war cakes was fined for ‘discrediting’ the Russian army too. Anastasia Chernysheva began sharing images of her cakes on social media soon after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last year.

Some of the cakes were decorated in the yellow and blue of the Ukrainian flag, while others had anti-war slogans or symbols. The baker was detained by officers, the human rights monitoring website OVD-Info has reported, citing her lawyer.

These are only a number of appalling and ridiculous cases which are sure to increase, forcing members of the media like Ms Starostina, and several of her colleagues to leave the country today. Valery Fadeyev the chairman of Russia’s ‘Human Rights’ Council, has proposed to define the concept of “Russophobia” at legislative level and called for a law to deter it.

He declared: “Our task today is to try to formulate legally what Russophobia is and what articles of the criminal code can be used under this qualification, and if there is no such article, then an additional article must be introduced”.

At least 500 journalists have fled Russia since its unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, according to Proekt Media, an investigative outlet, and are reporting the truth about the country’s disastrous war. They call this “offshore journalism”. The journalists are scattered across Europe, in cities such as Riga, Tbilisi, Vilnius, Berlin and Amsterdam, where they manage to reach a large audience, and most of them are under the age of 40. “Our job today is to survive and not let our readers suffocate”, said Ivan Kolpakov, the editor-in-chief of Meduza, a news website. Meduza has reported on the massacre of Ukrainian civilians in Bucha, and the extraordinary number of convicts that have joined Wagner, the mercenary group run by Mr Prigozhin, who is a crony of Mr Putin’s. It has emerged that for a period the Russian military cut off supplies of weapons and ammunition to Wagner, and this, too, is likely to have been covered by Meduza.

Mediazona, an online outlet founded by two members of ‘Pussy Riot’, a punk band which stages protest concerts, is trying to count the true number of Russian casualties. In 2012, three members of the band were all convicted of “hooliganism motivated by religious hatred” and each sentenced to two years’ imprisonment.

Mediazona has also found an ingenious way to work out how many Russians have been conscripted, by analysing open-source data on the unusually high number of marriages since mobilisation began. (Draftees are allowed to register their marriage on the same day as they are enlisted, and often do, since they don’t know when, or if, they will see their partners again). Mediazona estimates that half a million people have already been drafted—far more than the 300,000 the Kremlin said would be.

tv Rain, Russia’s best known independent television channel, went dark eight days after the war started. Echo of Moscow, a radio station with five million listeners, became silent on the same day. Soon after that, Novaya Gazeta, the most outspoken critical newspaper in Russia, stopped printing.

Alexei Venediktov, the editor of Echo, and Dmitry Muratov, the Nobel prize-winning editor of Novaya Gazeta, stayed in Russia while some of their former colleagues set up operations offshore.

tv Rain is back on air, now based in Latvia and broadcasting via YouTube to 20 million viewers a month (although it has been ordered to shut its terrestrial output by the media regulator), most of them inside Russia. Echo is in Berlin,streaming news and talk-shows live via a new smartphone app, which the Kremlin tried but failed to block.

Roman Dobrokhotov, who runs The Insider said: “There is plenty of demand for investigative journalism, there are people who know how to do it and there is no shortage of subjects to investigate”.

Officials never approved of the sort of investigative reporting such as I undertake, but the Kremlin did once tolerate niche media. Since February last year, though, it has built great walls around the truth, closing some 260 publications. Twitter, Facebook and Instagram are now blocked, accessible only via VPN proxies. As I have shown, laws ban discrediting the Russian army (punishable by fines as was suffered by Ms Starostina, or jail as Mr Moskalyov endured), or publishing ‘fake news’ (punishable by prison).

But people are getting round these laws, and even within Russia there is ground for hope, for example a new documentary film by independent journalist Jake Hanrahan has shed light on the “partisan” fight against the Kremlin.

He has produced a YouTube film, which interviewed two members of an “anarcho-communist” group known as BOAK, whose aims were vague and unrealistic before the invasion of Ukraine.

Fires that have broken out across Russia have been blamed on Ukrainian saboteurs and even Western intelligence operatives, according to Radio Free Europe, but Mr Hanrahan suggests a “large-scale, active resistance inside Russia” is now active.

A list, updated on December 1, criminalises any discussion of over 60 sensitive subjects, from the numbers of Russians killed in action to the country’s mobilisation campaign, and anyone who wants an alternative view has to search hard for it. It is difficult to find a VPN that the security services haven’t already blocked.

The fact that there is now a free media (although largely outside the country), should be saluted, however it is WRONG that they had to leave Russia IN THE FIRST PLACE, and it only serves to highlight the awful issues facing other journalists around the world, when they have tried to report facts.

Recently came more worrying news. After a significant escalation in state-backed threats from Iran and advice from the Metropolitan Police (Met), Iran International TV (IIT) was forced to close its London studios, and move broadcasting to Washington. Managers said that threats had grown to the point that it was no longer possible to protect the channel’s staff, other employees at Chiswick Business Park, and the general public.

IIT was warned by UK authorities in November that its journalists were under threat from Iranian agents and the Met took measures to strengthen security around the network’s office in the area.

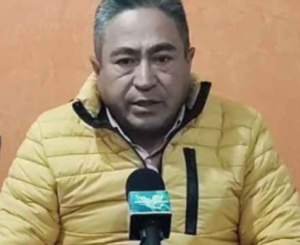

Elsewhere, a video journalist called Eduardo/Roberto Toledo died of his wounds in Mexico, after being shot by three armed men on his arrival at the office. He was the FOURTH journalist to be murdered in the country in just ONE month! Mr Toledo was killed in the city of Zitácuaro, where he reported for a local news outlet, Monitor Michoacán, and the region is rife with violence, as drug cartels and criminal groups fight to control illegal logging.

The media freedom organisation Reporters Without Borders has said that 47 journalists were killed over the past five years in Mexico (the same number as in Afghanistan), but even more than that ghastly figure is those missing (presumed kidnapped), and reporters who are forced to wear bullet-proof vests while they do their jobs. But this level of protection didn’t save one journalist in Mexico. Lourdes Maldonado was shot dead in Tijuana.

In Belarus (which is seen as an ally of Russia during the war in Ukraine) the situation is also terrible. At least 16 journalists are behind bars in the country, and riot police are singling out reporters for arrests and beatings at protests as the media is intimidated.

The embattled dictator there, Alexander Lukashenko, forced a Ryanair passenger plane to make an unscheduled stop in his capital Minsk, in order to arrest the editor of an internet channel, NEXTA, that has been reporting on his crackdown.

Roman Protasevich, aged just 26, was taken off the plane, which was flying from Athens to Vilnius, the Lithuanian capital. Citing what it said was ‘evidence’ that there were explosives on board, the authorities forced the aircraft to land in Minsk as it passed through Belarusian airspace on its way to neighbouring Lithuania, sending a MiG fighter plane to escort the Ryanair jet down. The state news agency later reported that no explosives had been found, and it seems certain that the incident was invented purely as a way of arresting the journalist.

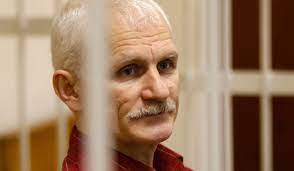

His detention came before the human rights and democracy activist Ales Bialiatski was found ‘guilty’ of financing protests by a court in Minsk and sentenced to 10 years in prison, after a trial labeled a “sham” by the US and EU.

This followed the clampdown reported on by Mr Protasevich, following the anti-government demonstrations that started in the summer of 2020 and continued into 2021. Three other activists were also sentenced to a combined 24 years in jail.

This worrying news hit the headlines after Marina Zolotova, the editor of Tut.by, an independent news website in the country, said: “Blue press jackets and press badges have become targets. When journalists go to cover a protest they cannot be sure that they will come home. This is a real war by the authorities against independent journalism and their own people.” It is clear that Mr Lukashenko is waging a war against journalists who have dared to report on his regime’s brutal crackdown against peaceful protesters. At least eight demonstraters have been killed and hundreds more have alleged torture and rape in police custody, while members of the media there are at risk of arrest (or worse) if they report this awful news. Among the most high-profile of those in prison is Yekaterina Bakhvalova, who was arrested as she filmed riot police firing stun grenades into a crowd demonstrating against the death in police custody of a protester.

In many countries it appears to be becoming worse for media freedom and investigative journalists like me, as well as reporters on The Eye. In total the US Press Freedom Tracker, a non-profit project, says it is examining more than 100 “press freedom violations” at protests. About 90 cases involve attacks.

In Russia the independent media is now very small, but an example of it (apart from Dozhd) is a special website which is devoted to the numbers that have been killed. Sometimes the persecution has official backing. Mr Putin recently signed a law that will allow Russia to declare journalists and bloggers “foreign agents” in a move that critics say will allow the Kremlin to target government critics. Under the vaguely worded law, Russians and foreigners who work with the media or distribute their content and receive money from abroad would be proclaimed ‘spies’, potentially exposing journalists, their sources, or even those who share material on social networks to foreign agent status. RT (Russia Today) stands accused of being a mouthpiece for Mr Putin, and by the mid-2000s Russian news shows’ agendas were being set at government-led meetings.

Even in the UK, there is cause for concern.

Privacy laws are starting to rival libel rules (which are known for their ferocity around the world) in hampering free journalistic inquiry. The UK’s Supreme Court (which was in the news ruling out an independence referendum in Scotland) has confirmed an award of £25,000 in damages against the media giant Bloomberg because (it was claimed) an individual’s privacy had been invaded by publication of details from a criminal inquiry into the activities of an American businessman. In doing so the court has tilted UK law further away from freedom of the media, and towards privacy rights.

The rise, too, of social media, has allowed to grow stronger the shrill abuse of the kind of news I publish. In the past I have been called online (wrongly), a “bastard”, a “liar”, a “misogynist”, a “little git”, and (accurately), a “troublemaker”, a “nuisance”, “irritating”, as well as “annoying”.

But at least I haven’t been punished (or worse) for explaining my anti-war tattoo, or because of my daughter’s picture…

The memories of Phil’s extraordinary decades long award-winning career in journalism (when he could operate in a free environment) as he was gripped by the rare neurological disabling condition Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in a major book ‘A Good Story’. Order it now.

Regrettably publication of another book, however, was refused, because it was to have included names.

Tomorrow – disturbing news that the police have still not learned from a “calamitous litany of failures” in one high-profile murder case (meaning this service in London could have missed other ones, according to a damning watchdog report), puts centre stage how officers acted at the biggest force in Wales, which was at the centre of the Ely riots.