- Chinatown - 10th March 2026

- Dark speak easy part two - 9th March 2026

- Cyber bullying - 6th March 2026

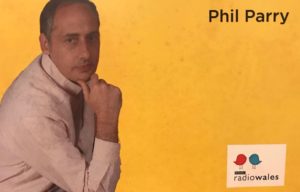

After 23 years with BBC Cymru Wales (BBC CW), and 38 years in journalism (when he was trained to use clear and simple language, avoiding jargon), here our Editor Phil Parry looks at the lack of sexual equality in newsrooms and beyond.

After 23 years with BBC Cymru Wales (BBC CW), and 38 years in journalism (when he was trained to use clear and simple language, avoiding jargon), here our Editor Phil Parry looks at the lack of sexual equality in newsrooms and beyond.

In the past he has described how he was assisted in breaking into the South Wales Echo office car when he was a cub reporter, recalled his early career as a journalist, the importance of experience in the job, and made clear that the ‘calls’ to emergency services as well as court cases are central to any media operation.

He has also explored how poorly paid most journalism is when trainee reporters had to live in squalid flats, the vital role of expenses, and about one of his most important stories on the now-scrapped 53 year-old BBC CW TV Current Affairs series, Week In Week Out (WIWO), which won an award even after it was axed, long after his career really took off.

Phil has explained too how crucial it is actually to speak to people, the virtue of speed as well as accuracy, why knowledge of ‘history’ is vital, how certain material was removed from TV Current Affairs programmes when secret cameras had to be used, and some of those he has interviewed.

He has disclosed as well why investigative journalism is needed now more than ever although others have different opinions, how the pandemic played havoc with media schedules, and the importance of the hugely lower average age of some political leaders compared with when he started reporting.

I have heard it said that journalism is the most equal profession in the world, and how ANYONE who brings in a good story (whether man or woman) will be treated with great respect.

This is in fact completely disingenuous.

During my long career in journalism, it became obvious that a very real divide existed between men and women.

In all the newsrooms I have worked in, women were usually given ‘softer’ stories involving children or animals, while the men were given ‘harder’ stories like murders or car crashes, when grieving friends or relatives had to be interviewed in a ‘death knock’ (the practice of knocking on the door of a deceased’s family member or friend).

There was also rampant sexism in the way women were treated by those in charge, and by the male reporters.

An attractive woman faced being leered at, while an unattractive one was laughed about.

There were very few women in the newsroom when I started as a trainee reporter in 1983 on the South Wales Echo (then the biggest-selling paper produced in Wales), and one wrote a light conversational column, while another did ‘soft’ advertising features (for which businesses would pay to have control of the copy).

No women whatsoever rose above the basic reporter or sub-Editor levels, to run the news desk, subs desk or become assistant editors!

Yet this was incredibly harmful, not simply for the women in question, but also for the media outlet, as well as for wider society. It still happens to a lesser extent today.

New academic research shows that even now around the world, 63 per cent of women journalists have been confronted with verbal abuse, and 80 per cent of women say they have suffered ‘manterrupting’ at work.

Men are also, too, the main subjects of stories, and the same research reveals that males represent 75 per cent of news sources.

This sexism is not even, however, and some countries around the globe are worse than others.

In “The First Political Order: How Sex Shapes Governance and National Security Worldwide”, the authors rank 176 countries on a scale of 0 to 16 for what is called the “patrilineal/fraternal syndrome”.

This is a composite of such things as unequal treatment of women in family law and property rights, early marriage for girls, patrilocal marriage, polygamy, bride price, son preference, violence against women and social attitudes towards it (for example, is rape seen as a property crime against men?).

Rich democracies do well: Australia, Sweden and Switzerland all manage the best-possible score of zero.

But Iraq scores a woeful 15, level with Nigeria, Yemen and (pre-Taliban) Afghanistan – only South Sudan does worse.

Dismal scores are not limited to poor countries either (Saudi Arabia and Qatar do terribly), nor to Muslim ones (India and most of sub-Saharan Africa do badly, as well). Overall, it’s estimated that 120 countries are still to some degree swayed by this syndrome.

There are, though, grounds for hope.

Newsrooms are not what they were (although they are still not totally equal), and women are (rightly) treated with greater respect in most societies.

A randomised controlled trial with 1,200 Ugandan fathers found that major efforts have resulted in a measurable drop in domestic violence.

For example – Emmanuel Ekom, used to come home drunk and quarrel until morning, according to his wife, Brenda Akong, but now he does jobs he once scorned as women’s work, such as collecting firewood and water. One day she came home and discovered him cooking dinner.

Perhaps in future it may also be seen as entirely normal for women reporters to be given exactly the same jobs as men.

You never know!

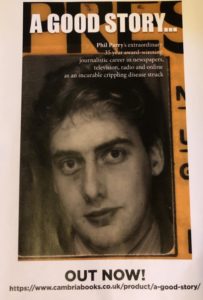

The memories of Phil’s astonishing decades long award-winning career (when men and women were given different stories) as he was gripped by the rare neurological disabling condition Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia (HSP), have been released in a major book ‘A GOOD STORY’. Order the book now!

Regrettably publication of another book, however, was refused, because it was to have included names.